By Sophia Lennox ’24

Majors: History and Art & Art History; Minors: Gender Studies and Museum, Field, & Community Education

Contributor Biography: Sophia Lennox is a senior majoring in History and Art History, and minoring in Gender Studies and Museum, Community, Field education from West Windsor, New Jersey. She enjoys exploring human connection, historical context, and personal influence in different forms of art.

Brief Description: This paper looks into the life and historical context of the incredible portrait painter, Suzanne Valadon, and how her work is influenced by her experience as an artist model in 19th century Paris. When she painted nude women, she had the first-hand experience of being in the model’s position, and her empathy, respect, and lived experience aided her in representing women naturalistically and with humanity. Valadon painted women that she knew and loved, and her portraits capture a distinct familiarity. In this paper, I explore specific paintings in which Valadon expressed womanhood, human relationships, and connection.

The following was written for ART 394-10: Abstract, Dada, Surrealism

Over the span of her productive and successful life, Suzanne Valadon went through a number of transformative experiences that shaped her work as an artist. As a woman born in France in 1865, Valadon witnessed a huge shift in cultural ideas, values, and roles as French society transitioned into the twentieth century.1 Valadon’s artistic career started with charcoal drawings of her mother and son and developed into full oil paintings of various figures and scenes. In her paintings, Valadon often depicts intimate domestic scenes of full-bodied, lived-in people experiencing daily life. Although some scholars, such as Rosemary Betterton, interpret Valadon’s work to be a rebellion from traditional painting, Valadon does hold onto some of the characteristics and tropes that are seen in traditional paintings of nude women. Valadon does not erase the artistic traditions or precedents of nude figures in many of her paintings, but instead, interweaves her unique perspective to build upon those traditions. In many of her paintings of nude women, Valadon represents the woman as an individual, firmly situating her within her environment. She is able to represent women comfortably and intimately in environments that typically are sexualized by male painters.

Valadon’s perspective is not unique solely because she was a female painter, there are a number of other female artists who worked at a similar time, such as Georgia O’Keeffe, Paula Modersohn-Becker, and Mary Cassatt. Valadon’s social and economic status dictated everything in her life growing up, as she was born to a single, impoverished woman living in Western France. To ease her family’s financial burden, she began to work at the age of nine. Valadon’s experience growing up in poverty is often cited as evidence to explain her ability to paint faithful portrayals of low-income people.2 Valadon continued to work a variety of jobs until the age of fifteen, when she began to model for artists in the Parisian district of Montmarte.3 Valadon attracted the attention of many artists, and she became an incredibly successful and experienced model over a span of ten years. Her time as a model transformed her trajectory in life and gave her an intimate view of the talents and techniques of some of the top Parisian artists. In France during this time, access to art education was immensely restrictive for women. Even if she had the financial means to attend a private school that accepted women, live anatomical sessions were strictly banned.4 Therefore, while she was modeling, she had a special opportunity to learn that she would not have had otherwise. Additionally, her experience as a model gave her a deeper understanding of the male gaze. She was posed in a number of different positions and would stay in place while artists would create an idealized, male view of her body on the canvas. Although historians believe that Valadon did not feel exploited by the artists that painted her5, due to her role as the model, her perspective was not depicted in the painting, but the male artist’s. As Valadon transitioned from a model to a full-fledged artist in her own right, she brought her experiences to her new work.

It is important to note that although I believe that much of Valadon’s work is informed by her experiences growing up in a low social class, her role as a model, and all of the other information that is known about her, it is important not to rely solely on her biography. For one, Valadon was known to embellish and fabricate aspects of her life to develop an alluring story,6 which pulls into question what is and is not accurate. Additionally, all we know about Valadon’s life is from the surviving written and artistic record of her life. A person experiences thousands of moments every day, any number of which may spark inspiration that we would never know about unless they wrote it down.7 Due to the especially limited records surviving about and by Valadon, it is impossible to capture the artist in her entirety and say with certainty that a painting was directly inspired or developed from something specific about her life. However, using some proven biographical information, and an understanding of some of the experiences Valadon may have had due to her class, identity as a single mother, and role as a model, there are some clear influences and connections that can give insight into Valadon’s work.

A distinctive feature of Valadon’s work is her ability to capture realistic and intimate portrayals of the women that she painted, instead of idealized bodies, and altered or enhanced feminine features for male enjoyment. Her 1916 painting, Nude Arranging Her Hair [Fig. 1], shows a nude woman in front of a dark green drape beside a side table with a small collection of objects on it. The woman is standing very comfortably, holding her weight on her straightened left leg, with her right leg bent to balance her, as she brushes her hair with a comb. The green undertones in the woman’s skin in Valadon’s painting parallel the green backdrop, situating the woman within the environment and connecting her to her surroundings. She is standing on top of white fabric, as someone might do if they had just removed their clothing.8 Although the woman is nude and in private, there is no seductive nature to her position. This stands in stark contrast to the woman in Pierre Bonnard’s painting Tall Nude [Fig. 2]. Bonnard was a French male artist working and living at a similar time to Valadon, but his portrayal of the female nude held a closer connection to traditional understandings than the understandings of Valadon. In Tall Nude, the woman is standing very straight, with her chin and hips tucked in, and chest pressed out. Her arm is pulled back behind her, revealing more of her body than would be if her arm was by her side. This is a very unnatural position for a woman to be casually standing in by herself, and instead represents more of a male fantasy. Both of these images are clearly referencing an artistic tradition of obscuring the identity of a nude woman by obscuring her face and viewing her from behind but go about it in very different ways. Valadon poses the woman in a highly naturalistic way, reframing the tradition into something that makes sense as to why we see this woman the way we do. Bonnard makes no attempts at contextualizing why the woman’s face is obscured by shading it much darker compared to the highlights on the rest of her body. Betterton writes, “what Valadon tried to capture in her drawings was the intensity of a particular moment of action rather than a static and timeless vision.”9 This idea is exemplified in the comparison of the Valadon and Bonnard pieces. In Nude Arranging Her Hair, Valadon captures a specific intimate moment of an unidealized woman partaking in an uneventful routine, whereas the woman in Tall Nude, however, represents the ‘static and timeless’ aspect of Betterton’s analysis. The painting does not capture any sort of specific action or moment in time. She stands in front of a light blue room divider holding a large section of white fabric, by a small chair. If the fabric is meant to represent clothing that she had just taken off as it is in Valadon’s piece, then her pose is not realistic of actions that a woman takes when changing alone. Valadon’s understanding of how women interact with the world helps her portray them more realistically and familiarly than the representations by her male contemporaries, who may have a more imaginative or sexualized view of femininity.

Another intimate painting created by Valadon is her 1916 work, Seated Nude [Fig. 3]. In this painting, a nude woman is sleeping, almost curled up, in a draped chair. The expression on her face is peaceful and contented, and as is typical of Valadon’s work, the woman is in a comfortable and realistic position. Her head rests gently on her shoulder, supported by the backing of the chair, and she is slouched, sinking into her seat. Her position is not angled or contorted, but droopy and exhausted. The yellow and brown undertones in the woman’s skin again situate her closely with the background of the piece, emulating the color of the surrounding walls and floor. Valadon does not idealize the woman’s body, allowing her stomach to rest naturally and comfortably as it would have for a woman reclining in this position. Similar to Nude Arranging Her Hair, the woman in this painting is in a vulnerable position, but she is not depicted sexually. Art historian Patricia Mathews notes that many of Valadon’s paintings lack a dominating sexual charge to them. Her works are often completely unsexualized representations of women, and instead, she focuses on routine and raw examples of the female experience.10 For her models, Valadon often used the people close to her, including her friends, family and domestic staff that worked in her home.11 These connections may have allowed Valadon’s models to be more vulnerable and trusting when they were posing for her, and helped Valadon’s work express a sensitive and warm quality. Valadon’s personal experiences also dictate how she views and represents her models when they are in a vulnerable position. As a woman who posed for many paintings, Valadon directly understands the situation that her models are in. She can personally relate to how they are posed and what they might be feeling and can use that experience to develop better connections with her models. She directly subverts the typical artist-model dynamic through her relationships with her models. Betterton describes the typical relationship as, “a ‘natural’ elision of the sexual with the artistic: the male artist was both lover and creator, the female model both his mistress and his muse.”12 Because, in the case of Seated Nude and other female nudes by Valadon, both the model and the artist are women. There is no room for the dominating ‘male creator’, and the connection between a sexual relationship and artistic creation is not there.

Valadon’s painting Two Bathers [Fig. 4] highlights a tender, caretaking moment between two women. The painting depicts two nude women, in which the carer sits on the top step of a small staircase, legs carefully bent, with the other woman sitting on the lower step just in front of her legs. The woman in front is sitting loosely curled up with her fingers interwoven and resting on her knees. The woman in the front appears to have a concerned, or disappointed look on her face. Her eyes are pointed downward, and her eyebrows come in together at the center. The woman in the back has a much softer expression, possibly concerned, but in a more attentive way than the lady in the front. This is another example of Valadon’s ability to portray a meaningful, unsexualized moment. Valadon allows these women to retain the curves and natural shapes of their bodies and does not flatten or idealize them, referencing Valadon’s value in capturing the specificities and intensities of real life.13 During Valadon’s time as a model, she gave birth to a son, Maurice. As he got older, Maurice struggled severely with mental health issues and alcoholism. Valadon was very attentive to Maurice during this period and helped take care of him throughout her life. Valadon’s experience growing up with a single mother, and then becoming a single mother herself, especially to someone who struggled with mental health, may have also helped her develop a painting that displays a meaningful caretaking relationship.

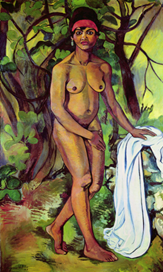

Valadon’s 1916 painting, Black Venus [Fig. 5], is one of only two surviving paintings that she created about black women, although there is a record of three other unlocated paintings.14 In the painting, the woman stands somewhat awkwardly, supporting herself on both her outstretched right leg and a straightened left arm. Her legs are crossed, with her front leg coming forward almost to protect herself from the viewer. Her right arm stretches over her hips with her hand covering her body protectively, almost possessively. Unlike many of Valadon’s other nudes, this woman does not appear to be relaxed and vulnerable, but instead very firm. This position from the woman may be her claiming a sense of autonomy because black women were prevented from having control over their bodies. Valadon valued the individualization of her figures in her paintings, and actively attempted to portray her figures as people.15 About this painting, Professor Suzanne Singletary from Thomas Jefferson University writes that Valadon “cast[s] the black female body—a highly contested subject, associated at the time with slavery, colonialism, and hyper-sexuality—in the role of Greek goddess.”16 Valadon paints this woman with a sense of humanity and ownership over herself that many other artists did not afford black women. Comparatively, in Henri Matisse’s Blue Nude [Fig. 6], the woman depicted is highly contorted, and a caricature of an African woman. Whereas the woman in Valadon’s painting is staring right at the viewer, the woman in Matisse’s is looking down. The expression on her face is squished, and she appears deeply concerned. The proportions of her body are twisted and molded, so much so that her position is unnatural and unrealistic. The woman in Valadon’s painting is not physically fetishized like the woman in Matisse’s painting, and instead is likened to something higher than human – a Greek Goddess.17 However, while many of Valadon’s other nude figures are depicted in domestic settings, the woman in Valadon’s painting is situated in natural surroundings. Metropolitan Museum of Art curator, Denise Murrell writes, “…The motif of the Black body in and as nature has been entwined with the dichotomy of nature ever since the seventeenth century, so it is difficult to view the setting as neutral ground.”18 Valadon is using another art historical precedent, but this time seemingly contradictory to the woman being likened to a Greek Goddess. How can Valadon provide the woman in the painting with ownership of her body, more so than her male contemporaries, while simultaneously situating her within a fetishized historical precedent that associates Black women with ‘tropical environments’ or as being ‘primal and primitive?’

Additionally, Valadon’s paintings in which the subject is fully clothed can be equally as revealing as her paintings depicting nude figures. The woman in Valadon’s The Blue Room [Fig. 7] is shown comfortably laying on a bed surrounded by a blue floral drapery. The woman’s pose is reminiscent of the popular artistic trope of the reclining female nude, however, it is immediately subverted by her clothing and her tone. Her pose is very comfortable and relaxed, just as she would be laying if she was alone in her room. Many paintings by male artists, as discussed earlier with Bonnard’s Tall Nude, instead have their models intricately and tightly positioned, regardless of how accurate that is accuracy to a woman’s actions when alone. She is wearing green and white striped pajama pants and a pink strapped tank top. An outfit like this is what a woman realistically might have worn to relax in her bedroom or around her house, instead of lounging in a tidy and fashionable outfit, or without clothes at all. It is additionally striking because Valadon uses color echoing in the undertones of her figure’s skin to help connect her nudes to their backgrounds. Not only does the woman’s clothing prevent her from making those connections, but she selected bright green stripes in her pants to further disconnect from the softly laid and flowing sheets. Instead of capturing her exclusively for her body and the male idealized view of a woman lounging around in the nude, the woman in the painting shows a holistic and realistic view of a woman. She has books at the foot of her bed, suggesting not only that she reads but that she is intelligent enough to understand them and read them leisurely. Additionally, she has a cigarette in her mouth, which was considered a masculine habit in France at this time.19 Here, Valadon is directly challenging the generalized understanding of women, and the roles of masculinity and femininity. People are used to seeing women posed in this position without clothing, so the addition of clothing, especially with striking and clashing patterns, asks the audience to think about the female nude.

Over her career as an artist, Valadon created an immense number of paintings and drawings. She had the ability to produce individualized, realistic, and human depictions of the women she painted nude. Her experiences growing up in poverty and within her social class in France helped her to create paintings that allow viewers to see what intimate moments in the lives of the lower class may have looked like. She was able to highlight experiences that were not often painted. Because she did not have access to formal art education, her perspective and techniques were developed through watching and experimenting while working for other painters as their models. However, a lack of formal education did not mean that Valadon’s paintings lacked knowledge of formative art history. Valadon was able to paint images that were aware of art historical traditions, while also using her perspective to set up her scenes to produce an image that was additionally aware of the experiences of women. Although Suzanne Valadon received attention and success during her lifetime, before very recently, there was a lack of substantial contemporary scholarship about her and her work. Due, in part, to the 2021 Barnes Foundation exhibition, Suzanne Valadon; Model, Painter, Rebel, there has been a resurgence in interest in Valadon’s work, which will hopefully begin to give Valadon the critical and academic interest that she deserves.

Figure 1: Suzanne Valadon, Nude Arranging Her Hair, 1916

Figure 2: Pierre Bonnard, Tall Nude, 1907

Figure 3: Suzanne Valadon, Seated Nude, 1916

Figure 4: Suzanne Valadon, Two Bathers, 1923

Figure 5: Suzanne Valadon, Black Venus, 1919

Figure 6: Henri Mattise, Blue Nude, 1907

Figure 7: Suzanne Valadon, Blue Room, 1923

Bibliography

Betterton, Rosemary. “How Do Women Look? The Female Nude in the Work of Suzanne

Valadon.” Feminist Review, no. 19 (April 1985): 3–24. doi:10.2307/1394982.

Childs, Adrienne L., Nancy Ireson, Lauren Jimerson, Denise Murell, Ebonie Pollock.

“Disrupting Tradition: Suzanne Valadon’s Black Venus”, March 22nd, 2021, Suzanne

Valadon; Model, Painter, Rebel, 30-41.

Dube, Ilene. “Model, Rebel, and Painter, Suzanne Valadon Defied the Odds.” Hyperallergic,

October 22, 2021. https://hyperallergic.com/685286/suzanne-valadon-model-painter-rebel/.

Ireson, Nancy, “Locating Suzanne Valadon”, in Suzanne Valadon: Model, Painter, Rebel, 8-17.

Philadelphia: The Barnes Foundation, 2021.

Jimerson, Lauren. “Defying Gender: Suzanne Valadon and the Male Nude.” Woman’s Art

Journal, no. 40, (Spring/Summer 2019): 3–12.

Lipton, Eunice. “Representing Sexuality in Women Artists’ Biographies: The Cases of

Suzanne Valadon and Victorine Meurent.” The Journal of Sex Research, no.27 (2019): 81–94.

Mathews, Patricia. “Returning the Gaze: Diverse Representations of the Nude in the Art of

Suzanne Valadon” The Art Bulletin 73, no. 3 (September 1991): 415–30. doi:10.2307/3045814.

Myers, Nicole. “Women Artists in Nineteenth-Century France” The Metropolitan Museum of

Art. September 2008. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/19wa/hd_19wa.htm#:~:text=While%20life%20dra

wing%20classes%20were,mores%20of%20proper%20young%20ladies.

National Museum of Women In the Arts, “Nude Aranging Her Hair”, Collection;

Suzanne Valadon. Accessed October 26th, 2022.

https://nmwa.org/art/collection/nude-arranging-her-hair

Nead, Lynda. The Female Nude: Art, Obscenity, and Sexuality. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Nochlin, Linda. Bathers, Bodies, Beauty: The Visceral Eye. Cambridge, Mass.:Harvard

University Press, 2006

Perromat, Prune. “Suzanne Valadon: The Model Who Became a Master Painter.”

France-Amérique, November 4, 2021.

Rose, June. Suzanne Valadon: The Mistress of Montmartre. London: Richard Cohen Books,

1998.

Salon Des Beaux Arts, “Suzanne Valadon”, Accessed October 25th, 2022

http://www.salondesbeauxarts.com/suzanne-valadon-salon-beaux-arts/

Saltzman, Lisa. “Mysterious Writings: On Lee Krazner’s Little Images and the Language of

Abstraction” in From the Margins: Lee Krasner/Norman Lewis, 1945-52, New York: The

Jewish Museum/New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2014, pp. 68-77

Singletary, Suzanne. “The Many Faces of Suzanne Valadon.” ArtHerStory, December 2021.

https://artherstory.net/the-many-faces-of-suzanne-valadon/.

Vincent, Jean. “Suzanne Valadon’s Blue Room – Part 1.” Thinking About Art, 2009.

http://thinking-about-art.blogspot.com/2009/06/suzanne-valadons-blue-room-part-1.html.