By Dante Chavez ’24

Major: English; Minors: Computer Science, Creative Writing

Contributor Biography: Dante Chavez ’24 is a current senior at Washington College majoring in English with a concentration in Creative Writing and minoring in Computer Science. He is from Baltimore, MD and currently works on campus at the Rose O’Neill Literary House as the Social Media & Marketing Intern. He enjoys and likes to think critically about all types of media from books to TV to video games and would like to take what he’s learned at Washington College to create his own piece of media one day.

Brief Description: Despite having a sizable audience, a decades-long history as a well-established magazine and a presumed demand, the WWE magazine was unceremoniously discontinued in the fall of 2014. In this project, I explain contributing factors of if not, exactly how this discontinuation came to pass. To accomplish this, I analyze the publication’s history from a variety of angles. Primarily, I study the November 2007 and October 2014 editions of the monthly publication, otherwise known as the 500th anniversary issue and the final issue respectively. These two editions provide perspective of how the magazine was marketed and how it performed at a relative summit of its publication history and at the end of its run. I also study official press releases made by the WWE relating to important milestones in the publication’s history to see how the company outside of the magazine division regarded and promoted the magazine. Finally, I look at the quarterly reports of the company’s finances to observe how the magazine was performing as a financial asset to WWE at various points throughout its history. All of this research is done in the hopes of constructing a coherent story of what led to my childhood magazine’s abrupt cancellation.

The following was written for ENG 460: Book History

- Introduction

Upon introduction to this project, I immediately saw it as a chance to catch back up with the monthly magazines I read the most when I was a kid and answer some burning questions I always had about the way they upheld their publication. Those two magazines were Highlights and the subject of this essay, the WWE Magazine published, of course, by wrestling promotion World Wrestling Entertainment. Shortly after beginning to research these two options, I found out that only the Highlights magazine is still in publication whereas the WWE Magazine had been discontinued in 2014 (aside from the WWE Kids Magazine offshoot that is still in publication in the UK). While having the Highlights magazine as a subject for this paper potentially allowed for an interesting exploration of the notions of authorship as it relates to minors, I found myself more immediately responsive to the subject of the WWE magazine due to its discontinuation.

As a former reader of the magazine and a long-time fan of WWE’s television and pay-per-view products, I couldn’t help but feel a sense of initial disappointment upon discovering that the magazine was no longer in publication. I wondered how the magazine had stayed so under the radar that I didn’t hear about its cancellation until nearly a decade after the fact, especially since in the time that had passed, I had been following the endeavors of the WWE on-and-off of their television programs so closely. From the WWE draft in 2016, which led to a complete restructuring of WWE’s two main TV programs, Monday Night Raw and Friday Night Smackdown, to the firings of specific performers and the reasons therefore, and even to WWE’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on not only the performers, but the way the WWE is run, I had been up to date with the major and minor events alike that had affected the company and its product. Yet, somehow, in my steadfast consumption of all the company’s endeavors, I missed something as major as the discontinuation of my cherished childhood magazine. How did this happen? What had made what I recognized as such a pivotal publication in my childhood so irrelevant that it went out without so much as a celebratory special final issue or even a public announcement from WWE themselves? This is what I set out to investigate.

- Research Question

In order to tell the story of the magazine’s demise, as this paper aims to do, it is important to understand the path the publication took leading up to it in order to contextualize some of the fatal changes the magazine underwent. Firstly, for readers who are completely unaware of what the WWE even is, WWE, or as older readers may know it, WWF, is the world’s largest brand of professional wrestling, an entertainment form in which men and women perform choreographed fights over the course of and for the sake of elaborate storylines that are presented as genuine. I mention the former name of the company because that is where the story begins, as the WWE Magazine was first published under the name of WWF Victory Magazine as a bi-monthly “fan publication” (WWE, “WWE® Magazine Looks To The Future”) in September 1983, before shortly being adopted by the company as their official magazine in the April/May 1984 edition and renamed to the WWF Magazine.

Now under the company’s direct control, it didn’t take long before the publication began to reflect the values of the product being presented. These values included portraying the male performers as legitimate athletes or, conversely, threats to those athletes and portraying the female performers as the sex appeal of the product. For the better part of its entire history, WWE found a lot of success in catering to a mostly male audience; this resulted in the role of women in a WWE ring being often reduced to that of “eye candy” for the men to ogle at in between the actual storylines going on. Proof of this trend first shows up in the magazine in the December 1984 issue in the form of performer Wendi Richter becoming the subject of the first women’s photoshoot of the magazine or, rather, what the October 2007 issue of the magazine fondly recalls as a “sexy pictorial” (6). The magazine continued operating with this foundation for much of the 80’s, 90’s and early 2000’s, along the way launching a second magazine entitled RAW Magazine in May 1996 designed to cater to more mature audiences, “promising to go where no sports-entertainment magazine had gone” (WWE, 500th Anniversary Issue 6), and then, four years later, publishing the first “Divas” issue, boasting four different covers featuring bikini-laden female performers. Despite the raunchier content, the magazine actually underwent its era of most cultural relevance during this time, boasting covers featuring cultural icons such as “Cyndi Lauper…Michael Jordan, Mike Tyson, and yes, Bart Simpson” (WWE, 500th Anniversary Issue 6). This era arguably lasted until the October 2007 issue of the magazine, otherwise known as the 500th Anniversary Issue. In the press release for this issue, WWE declared the magazine the “leading monthly men’s lifestyle magazine,” citing the publication ranking “fourth in newsstand revenue among men’s publications with more than $15 million in gross sales,” competing with names like GQ, Men’s Health and Muscle & Fitness and it being the “No. 1 sports title sold at Wal-Mart and Target stores nationwide” (WWE, “WWE® Magazine Looks To The Future”).

Less than one year later, in April of 2008, the magazine began to undergo a dramatic change with the launch of the WWE Kids Magazine. Later that year, in July, the WWE product would fully integrate this change by converting their presentation from that of one with a PG-13 rating to one with a PG rating. This move to cater to a new audience while sating a demand in the new market of younger readers represented a changing of ideals of the WWE product. Gone were the days of suggestive photoshoots of the female performers and in were the days of family friendly “posters,… puzzles and games” (Newsstand) in print. Five years later, the magazine would change once again as April 2013 brought about the digitization of the magazine in the form of the WWE Magazine App available for “iPad, iPhone, Android, Mac and PC” (WWE, “WWE Magazine goes digital”). However, this attempt to adapt to the contemporary and ever more digitized age of the internet would come in vain; a little more than one year later, the magazine would be unceremoniously discontinued after over 30 years in print in October 2014.

When I first began researching this topic, my first instinct was to make figuring out where in the chain of communication the magazine went wrong the subject of this paper. Soon after learning of this storied history, and having firsthand experience of the devoted fanbase of the WWE, however, the answer became quite obvious that it came down to the publishers: the WWE themselves. Though in their 2014 Annual Report they cite the “the continued overall decline in the magazine publishing industry” (35) as being the main cause for the discontinuation, a similar professional wrestling publication, the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, would go on to operate in print for nearly another decade, only recently announcing a shutdown of the mailed version of the publication this past November (Meltzer). This begs the question of how, despite having a sizable audience capable of surpassing 1 million subscribers on their streaming service, the WWE Network, in just the first year of its operation alone (WWE, 2014 Annual Report 1), an apparent demand for a wrestling publication as demonstrated by the success of the Wrestling Observer Newsletter, and a 30 year history as an established magazine of the genre, the WWE ultimately couldn’t capitalize on these elements and publish a successful magazine.

- Methodology

To investigate an issue as potentially complicated and messy as the end of a magazine, I knew I had to approach the subject of the magazine from a variety of angles close and far to the subject. Primarily, I decided to research what the company itself had attributed the failure of the publication towards. In lieu of anything that resembled any kind of official press release, this led me to the 2014 edition of WWE’s Annual Report addressed to its shareholders. As 2014 was the final year of the publication, I figured the WWE had to offer some kind of official explanation for the discontinuation to the people that most go towards supporting the company monetarily. Unsurprisingly, the front half of this report contains a lot of propagandic jargon and statistics that paint the company in a favorable light. However, I found that the back half of the report contained a much more objective perspective into how the company was actually financially performing during the time of discontinuation, as attached to the back is the Form 10-K WWE is legally required to provide its shareholders with. While WWE is still in control of the official statements found within the Form 10-K, the concrete facts they are legally mandated to provide about the performance of their business remain uninfluenced by the positive skew of the rest of the document. I found this to be an insightful yet dense look into how financially beneficial it was for the WWE to keep the magazine in publication.

My next strategy was to search for allies who were similarly investigative about the magazine. Frankly still shocked that there seemed to be no official press release concerning the end of the magazine other than a measly tweet thanking everyone for reading, I thought that perhaps there would be some other dedicated reader that did some similar research upon hearing about the discontinuation. The only document this search led me to was an article by John Corrigan, a writer for The Huntsville Times in Alabama, who similarly describes himself as a long-time fan of WWE’s products including the WWE magazine. However, besides a loving tribute to the magazine itself, the only point related to the discontinuation of it I could find in this article was the same defeatist explanation offered by that of the WWE of the decline of the magazine industry as a whole. While the figures he cites certainly aid his and the WWE’s argument, I ultimately found his explanation unsatisfactory in the face of the success of similar publications like the Wrestling Observer Newsletter or Pro Wrestling Illustrated, which Corrigan himself points to in the article.

Next, I figured I should be more practical in my research. After all, in researching how a magazine met its end, what better way is there to figure out how it died than to study the final issue itself? With the budget of the 40 dollars this project allowed for, I purchased the collector’s edition of the October 2014 issue of the publication from a collector on eBay to analyze the contents within the magazine and see if it could offer any hints about what could have contributed to the demise of the publication or, alternatively, to see if it was a worthy end to the historical run of the magazine. Quickly (or perhaps not quite quickly) enough, I realized I had nothing to compare the issue to and searched for a similarly landmark issue of the publication to draw parallels to. After further research, I decided the best issue to compare it to would be the October 2007 issue of the magazine also known as the commemorative 500th Anniversary Issue alluded to earlier in this paper. Since I was unable to find an archived version of the 2007 issue, and it was already past the deadline to request funds, I made a decision that I (quite honestly) really hope pays off and bought the 500th Anniversary Issue with my own money in order to have a parallel to compare the final issue to.

The final form of primary sources that I figured would be somewhat helpful in my research were the articles I could find on the official website of WWE, WWE.com. The first category of articles I thought to search for were press releases related to the magazine itself released at important moments throughout its relatively modern history. Of these, I found three standout announcements: one announcing a revamped version of the magazine, one promoting the aforementioned 500th Anniversary Issue, and one announcing the digitization of the magazine. I figured that these would give me an idea about how the magazine was referred to and promoted throughout different points of its publication period. The second category of articles I thought to search for were articles made around the same time as that of the discontinuation of the magazine in order to see not only if the quality of the reporting done on the website reflected that of the magazine but also to see if the type of content matched the general aesthetic of the kind of articles found in the magazine. I was also curious to see if there was any overlap between the articles written in the magazine and those featured on the website.

Finally, in terms of secondary sources, I tried to look for articles revolving around three topics: niche magazines like the WWE Magazine and their general success rate, the success of periodicals in the contemporary world, and what the symptoms of the decline of a magazine look like. However, I was only successful in finding articles that included two of the three of these topics despite many searches on OneSearch and Google Scholar. Unfortunately, this means that I could not find an authoritative source detailing the telltale signs of a dying magazine, but with the research I am armed with, I should be able to provide somewhat of a thorough theoretical autopsy of how the WWE Magazine died.

- Findings

Surface level research would lead one to the same conclusion the company itself came to. After all, as Corrigan reports, “the amount of net units (of the WWE Magazine) sold plunged from 6.4 million to 1.8 million over the past decade” prior to the end of the magazine’s run, whereas “before 2011, the publication generated revenue of at least $11 million” (Corrigan). WWE themselves even backs up this trend in their annual report as they admit that “digital media revenues, which include revenues generated from…our magazine publishing business, decreased by $7.8 million in 2014 as compared to 2013” (28) ultimately inspiring “cost reduction initiatives” (6) that led to the shutdown of the magazine, which the company attributes to “the continued overall decline in the magazine publishing industry” (35). Given this data, one could easily come to the conclusion that over the course of 2010’s, the magazine industry has just become less and less profitable, and, therefore, a successful magazine has become less feasible to maintain. While there is certainly some precedent to this argument, it has to be reiterated one last time that it simply doesn’t explain away the continued success of publications like Wrestling Observer Newsletter and Pro Wrestling Illustrated, which operate in the same genre as WWE Magazine. As a result, one would naturally come to the conclusion that there must be some deeper reason as to why there was such a drastic decline in sales of the magazine, and in my research, I believe I have uncovered three overlapping failures over the course of the final years of the magazine that led to its eventual discontinuation: a three count, if you’ll bear with me.

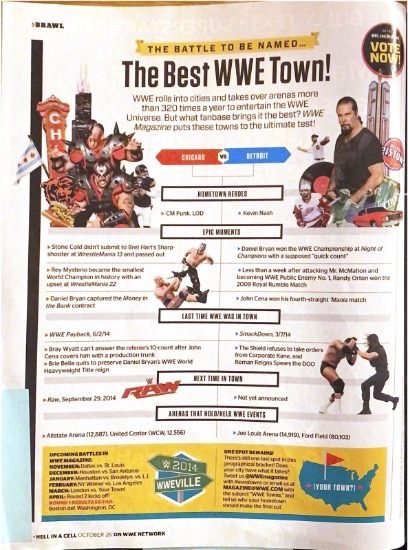

The most glaring of these failures is the company’s failure to successfully establish a new identity following the decision to begin catering to a younger audience. As previously stated in this paper, the WWE changed from a company that heavily catered to men to one that near instantaneously became family-friendly in the summer of 2008. This begs the question: “Where did this leave their ‘leading monthly men’s magazine’?” It turns out it left it with quite the identity crisis that makes itself very apparent in the actual pages of the publication. While perusing the October 2014 edition of the magazine, it’s not hard to find inconsistencies in tone and engagement with a target audience. On page 23, there’s an ad for WWE’s anti-bullying campaign, Be a Star, challenging kids to “make it through a day at school – with your favorite WWE Superstars,” while on page 25, there’s another ad for the Total Divas reality TV show, which caters heavily towards the older female demographic; finally, on page 28, there’s an entire feature on American football and what different performers think of the male-dominated sport (see figures 1-3). Within six pages of each other, the magazine hops between catering to three different demographics. When compared to the October 2007 issue of the magazine, these tonal inconsistencies stick out even more. Though the older magazine is lowbrow to the point where some features of it have not aged well, the tone is consistent the entire way through the magazine. On page 1, in the midst of the table of contents no less, the writers of the magazine proudly declare that the “Divas in Demand” section of the commemorative magazine, which features a two-page spread of four female performers in bikinis, is their favorite part of the job by posing the rhetorical question, “The best part of our job?” and answering “Taking these photos. Duh.” In case there’s any lingering confusion about who this iteration of the magazine is meant for, ninety pages further in, a feature entitled “Shut Her Down” details “WWE-style” ways to “silence a nagging lady,” (90) directly advising partnered men how to “shut down” a significant other. The editors even go so far with endearing themselves to this audience as to portray themselves as them. On page 96, in a feature entitled “Editor Hijinx 101,” the editors of the magazine depict themselves in scenarios akin to those one might find in a frat house (see figure 4). From a picture of an alleged prank where a coworker’s desk drawer was filled with foam, to a picture of the senior editor of the magazine in an American flag singlet and starred cape, the editors of the 2007 iteration of the magazine used this section to firmly establish their audience as a majority, if not strictly, male demographic. Establishing a core audience so boldly like this is something the 2014 version avoids doing during the entirety of its page length.

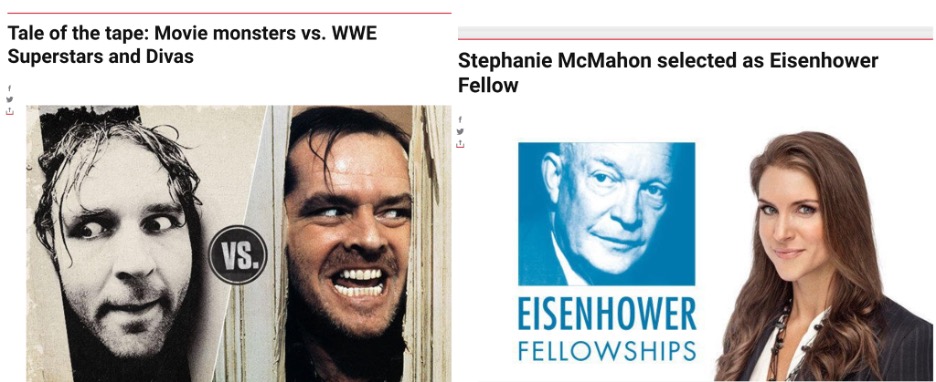

A failure to even pick a core audience and commit to it elucidates another failure of the WWE Magazine in its late stages: a failure to invest. By “failure to invest,” I do not necessarily mean monetary investment. Rather, I mean a failure to even invest enough effort into the production of this magazine. To show what I mean, as an experiment, I counted how many different other business ventures of WWE took up the page real estate of the final issue of the publication’s historic run. I came up with a final number of 9 different other endeavors, including video games, auctions, streaming services, and much more. I surmise that WWE and its performers’ attention was so split between all these other ventures that by the time it came to publish what used to be the “leading men’s monthly magazine,” there was barely anyone left to produce it. This makes itself evident in the magazine by just how little effort the stories included in it are. The October 2014 magazine’s main features include two Q&A’s with performers, a collection of Behind the Scenes photos most likely scrambled together at the last minute to create “The Last Will & Testament of the WWE Magazine” (50), and “The Future of WWE”, a meditation on the future of three rising stars in the WWE in which the future stars are not even interviewed but loosely compared to stars of the past. In comparison, the October 2007 issue takes its time to celebrate some of the most important features to ever be included in the WWE Magazine in a feature titled “Feature Presentation” (76). These features include a 2002 article breaking the story about one of those most infamous walkouts in the company’s history, that of Stone Cold Steve Austin after Wrestlemania X8, a June 1999 article about a pivotal change in WWE’s presentation, marking the beginning of a new era now known as the “Attitude Era,” and an op-ed written by one of the performers about the first time WWE held Tribute to the Troops, an annual event where the WWE often travels overseas to deliver a performance in front of armed forces. Meanwhile, the 2014 iteration of the publication apparently was not even allowed the luxury of purposefully being the final issue of the magazine, made evident by a typo on page 24, which advertises a tournament to decide “The Best WWE Town,” which was meant to continue in the upcoming magazines (see figure 5). On top of this, the WWE.com website had the ability to report on subjects of equal if not more relevance than the WWE Magazine could possibly report on in a fraction of the time (see figure 6).

This alludes to the third and final failure of the magazine’s late stages: a failure to adapt. Alongside reporting on more relevant events on their website than those featured in the magazine, the WWE made other crucial mistakes in their efforts to adapt the magazine to the digital age. According to Kevin Baker’s article, “How Niche Magazines Survive and Thrive Through an Industry in Turmoil,” there are three things a magazine in the digital age needs to value to prosper: “their reader devotion, their careful approaches to digitalization, and their use of paid digital content” (Baker 407). The WWE failed on all these fronts with their publication. I have already covered their lack of reader devotion at this point earlier due to their identity crisis, but the WWE also came up short in successfully managing the other two. I mentioned earlier in this paper that in April of 2013, WWE Magazine went digital via the WWE Magazine app. In addition to this, WWE appears to initially have given free content away in the form of a 30-day free trial subscription to the digital version (WWE, “WWE Magazine goes digital”). However, Baker advises that simply “giving this content away just (leads) to readers becoming accustomed to free access for magazine content, which makes it more difficult to maintain paid subscriptions” (Baker 408). Unfortunately, WWE did this twofold in the form of the free trial and the website itself offering the same quality of content. The raw data even matches the consequences of this that Baker warns against. Baker explains that “giving away free content may help bolster overall circulation numbers,” but “overall, though, it has the potential to negatively impact the title’s relationship with both readers and advertisers.” (Baker 408). This is reflected in the 2014 Annual Report as WWE reveals that “Total Digital Media net revenues were $20.9 million, $28.7 million and $25.7 million, representing 4%, 6% and 5% of total net revenues in 2014, 2013 and 2012, respectively,” which matches the expected relative increase in profits in 2013, the year the magazine went digital. Though I believe that all three reasons contributed to the magazine’s discontinuation in equal parts, this may just be the most important failure on the part of the publication, as the failure to ingrain itself in the contemporary world after so many reinventions in the past indicated a definitive inability for the magazine to evolve any longer.

- Conclusion

In my research, I believe I have come up with three very feasible reasons as to how and why the WWE Magazine ultimately met its end, despite the obvious lack of scholarly research into the topic. Doing this research in this sneakier and more roundabout way taught me to look for information in the unlikeliest of places, including tax filings, press releases, and, on rare occasions, potentially even typos in my sources. In my research, I have also educated myself on what it takes to run a successful magazine in the age of the internet and believe I can now recognize when a publication is doing well for itself in the digital space and when it isn’t.

Though I personally believe I have provided a comprehensive understanding of what led to the downfall of the publication, I would love to have known what insiders such as writers and editors thought about the magazine’s run. I also still don’t quite know the overall fan reaction to the discontinuation of the magazines. I would’ve loved to have found out whether the majority of fans thought it was an eventuality that it would be discontinued, whether they thought it came out of nowhere, or any other reaction I could be discounting.

On the topic of unknown elements of this project, there were a few shortcomings which, given more time, I would have looked into. One thing I definitely regret not doing is acquiring the first edition of the WWF Victory Magazine for some context about where the magazine started. Comparing its beginning to its end would have not only been poetic but have provided a fuller story of the magazine to contextualize its entire publication run. Given more time, my second instinct would have been to try to contact former editors of the magazine to ask them where they think the publication went wrong, as hearing from an authoritative source like the ones actually behind the magazine would have benefitted the legitimacy of this project immensely. One minor thing that I think could have aided this project is the inclusion of social media statistics of the WWE Magazine accounts across Twitter and Facebook as having these on hand would have helped to illuminate how popular the magazine was in relation to the overall WWE product as well as the general public’s reaction to the discontinuation of the publication. Lastly, I still wish that I had found a source detailing the traits of a dying magazine. In retrospect, however, I guess one could say that in studying this topic, I defined for myself those very traits.

Works Cited

Baker, Kevin M. “How Niche Magazines Survive and Thrive Through an Industry in Turmoil.” Publishing Research Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, 2018, pp. 407–416, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12109-018-9592-1.

Champions of Innovation: 2014 Annual Report, WWE, Stamford, CT, 2015, https://corporate.wwe.com/~/media/Files/W/WWE/annual-reports/2014.PDF. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

Corrigan, John. “Final Edition of WWE Magazine Hits Newsstands Today after 30 Years in Circulation.” The Huntsville Times, 16 Sept. 2014, https://www.al.com/entertainment/2014/09/final_edition_of_wwe_magazine.html. Accessed 9 Nov. 2023.

Hendrickson, Elizabeth. “Learning to Share: Magazines, Millennials, and Mobile.” Journal of Magazine & New Media Research, vol. 14, no. 2, Fall 2013, pp. 1–7. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edo&AN=91509166&site=eds-live.

Meltzer, Dave. “Updates for Wrestling Observer Newsletter Print & Online Subscribers.” Wrestling Observer Figure Four Online, Sports Illustrated Media Network, 6 Nov. 2023, www.f4wonline.com/news/updates-for-wrestling-observer-newsletter-print-online-subscribers#:~:text=That%20decision%3A%20the%20mailed%20version,be%20put%20on%20the%20website.

“New WWE Magazine Launches Today.” WWE.Com, WWE, 11 July 2006, https://corporate.wwe.com/news/company-news/2006/07-11-2006. Accessed 28 Nov. 2023.

United States, Congress, Division of Corporation Finance. Form 10-Q, World Wrestling Entertainment, Inc., 2014. https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1091907/000109190714000028/wwe-6302014x10q.htm. Accessed 21 Nov. 2023.

“WWE Kids Magazine.” Newsstand, www.newsstand.co.uk/106-general-magazines/11103-subscribe-to-wwe-kids-magazine-subscription.aspx. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

“WWE Magazine goes digital.” WWE.Com, WWE, 3 Apr. 2013, https://www.wwe.com/inside/magazine/wwe-magazine-goes-digital. Accessed 16 Nov. 2023.

“WWE® Magazine Looks To The Future As It Celebrates 500th Issue.” World Wrestling Entertainment Inc., 11 Sept. 2007, corporate.wwe.com/investors/news/press-releases/2007/09-11-2007.

WWE Magazine: The 500th Anniversary Issue, Oct. 2007, pp. 1–102. Issue 16.

WWE Magazine, Oct. 2014, pp. 1–80. Issue 105.

Appendix

Figure 1 (first): WWE Be a Star Ad (WWE, WWE Magazine Issue 105 23)

Figure 2 (middle): WWE Total Divas Ad (WWE, WWE Magazine Issue 105 25)

Figure 3 (last): “WWE Superstars Talk Pigskin” (WWE, WWE Magazine Issue 105 28)

Figure 4: “Editor Hijinx 101” (WWE, The 500th Anniversary Issue 96)

Figure 5 (top): “The Best WWE Town!” with an element in the bottom left advertising upcoming rounds in the tournament (WWE, WWE Magazine Issue 105 24)

Figure 6 (bottom): Two features on WWE.com both published on October 15, 2014, the same month as Issue 105 of the magazine (WWE.com)