By Torey Simpson ’24

Major: English; Minor: Museum, Field, and Community Education

Contributor Biography: Torey Simpson is from Harrington, Delaware with a special interest in book history and print culture. While at Washington College she was the President and small group leader of Intervarsity Christian Fellowship, a student assistant at the Rose O’Neill Literary House, a member of The National Society of Leadership and Success, and an inductee of Sigma Tau Delta, the International English Honor Society. She spent her summer breaks working at Camp Pecometh in Centreville, Maryland teaching nature discovery, archery, and challenge courses. After graduation Torey aspires to be a public or academic librarian and aid others in their educational and creative interests.

Brief Description: Inspired by The Bookwoman of Troublesome Creek, a novel by Kim Michele, this paper examines the Pack Horse Librarians of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression, who rode horses through the sparsely populated mountainous region to deliver resources and reading materials to families and one-room schoolhouses. Under intense economic pressure, the Pack Horse Librarians used knowledge of their patrons’ values and needs to influence their collection development. To prolong the circulating lives of the books and periodicals that were falling apart from frequent use, librarians would cut apart the most useful sections to put into scrap books to circulate. Using books as material objects, the physical attributes of a book can be analyzed to decipher how it might have been published, circulated, and received by the audience. This research may benefit current and future rural librarians to understand how to examine the community they serve and develop their collections to fulfill the needs of said community.

The following was created for ENG 460: Book History

Introduction

One summer, I read The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, a novel by Kim Michele Richardson. The protagonist of the story was a woman living in the mountains of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression and working as a pack horse librarian. Pack horse librarians were not something I had ever heard of and so they immediately sparked my curiosity. Reading the book, I found that instead of working in a library building, pack horse librarians spent most of their working hours riding horses through the sparsely populated mountainous regions to deliver reading materials to families and one-room schoolhouses. This library outreach program was very close to my heart because I grew up in a small town with no local public library. I was always so excited when, once a month, the bookmobile came to town, and I could find some new books to read. The bookmobile was from the closest public library about a thirty minute drive there and back, including however long it took to pick out a few books. Considering how big and busy my family was, going to the library was rarely possible. My elementary school had a library, but students were discouraged from checking the books out to take home. Overall, I had limited access to reading material at my level that interested me. I love how my excitement about the bookmobile was exactly what I saw reflected in some of the people in the novel when they saw “Book Woman” coming with new books.

When I was in seventh grade, my family moved to a larger town with a local library that I could visit far more often than the bookmobile came to town. Now, I had the ability to read as many books as my heart desired because I could walk to the library. Immediately, I got involved in the Teen Advisory Board and found that libraries do a lot more than lend out books. Not only are there DVD’s, magazines, and newspapers, but there are programs for people to participate in and stay active in the community. My interest in libraries only grew from there, and I currently plan to earn a Master of Library and Information Sciences degree and work in either public libraries, academic libraries, or archives.

The fall semester after reading The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, I was taking a book history and American print culture class. This was a unique course, as we were focusing on books as material objects instead of on the stories they hold. It was interesting to think about how the physical attributes of a book or any printed material could be analyzed to tell you about how it was published, disseminated, and received by the audience. Given my interest and experience with libraries, I thought the Pack Horse Library Project of eastern Kentucky would make a fascinating topic for a research project.

Research Questions

When I first started this research project, I simply wanted to learn more about what the Pack Horse Library Project was and had hope that there would be research questions worth asking. My first research question was, “What accessibility and reception did the isolated people of eastern Kentucky have for the reading material and the pack horse librarians?” I was interested in answering this question because both accessibility and reception are necessary for the library outreach program to be successful. The reading materials can be handed straight to the readers, but if people are not open to receiving and them, the materials are useless. However, that goes both ways, because people can be eager to read as many books as they possibly can, but if they have no access to the resources they crave, they will remain unfulfilled. The brick-and-mortar libraries, as well as the pack horse librarians, are fully capable of bringing reading materials to people, but how they get people to want to read is a big question I have always struggled with. In researching this question, I expected to find out how the program functioned and its effects on the residents it served, especially pertaining to their attitudes about reading or literacy rates.

However, as I continued to learn more, I decided to shift my research question to focus on how the pack horse librarians encouraged people to read, because I plan to be a librarian in the future. I changed my research question to, “How did the pack horse librarians add to, maintain, and edit their reading materials to appeal to their patrons?” My thought process was that people are more likely to want to read if there are available reading materials on topics they enjoy or agree with. Therefore, the librarians might have used the concept of supply and demand; seeing more people wanting to read certain topics would make the librarians want to obtain more materials on those subjects to encourage people to continue reading. I added “maintain” because this is a necessary aspect of keeping reading materials in circulation so more people can enjoy them. If there were materials that were more popular and borrowed multiple times over, they would eventually be damaged or worn out and need repairs.

With this research question, I was expecting to find out how librarians repaired, received, or bought supplies. I wanted to know who the largest donors were and if their beliefs and ideals affected the type of materials librarians were able to distribute to their patrons. I was also expecting to learn about any censorship that might have been taking place either by donor request, government law, parental restrictions, or other reasons. Looking into this question, I found the scrapbooks to be the answer for most of my questions, so it was time for another change in my research question.

This is how I landed on my final research question, “How do the scrapbooks made by the pack horse librarians display the print culture of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression Era?” The deeper I got into research, the more these scrapbooks were mentioned, which caused me to think they are under researched artifacts of their time and place. The scrapbooks act as primary sources of the work the pack horse librarians did and some have contributions from the residents of eastern Kentucky served by the project.

Pack horse librarians repaired their damaged reading materials by way of scrapbooks, which provided me an answer. However, with this topic as my final research question, I was still expecting to find out what affected the types of reading materials the pack horse librarians chose to add to the scrapbooks, if any censorship of reading materials added to the scrapbooks, and how the pack horse librarians decided to add to or make new scrapbooks to appeal to their patrons.

Methodology

I started the research process by using Washington College’s OneSearch database, but I hit a roadblock because of the lack of sources. As I was struggling to find any information on my own, I scheduled an appointment with Alexandria Baker, Director of Public Services and Faculty Librarian in STEM at the Miller Library, to get help finding useful sources. During my meeting with Ms. Baker, I needed to prove to her that the Pack Horse Library Project was a historical event and not fictional, since my research was inspired by a novel and information about The Book Woman of Troublesome Creek kept appearing in the search results. She believed it was factual when we found documentation saying it was funded in part by President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression Era. Another issue Ms. Baker and I had was the fact that different sources spelled “pack horse” differently. Some had “packhorse” as one word, others had it as two, and still more hyphenated the word as “pack-horse.” This made sources hard to find since the databases saw these terms as completely separate and would only show me results with the spelling that matched my search. This problem continued with the words “library,” “libraries,” and “librarian(s),” though this was an easier problem to solve; since they share a root we started using “librar*” to make sure they all showed up in the search results. By the end of our meeting, Ms. Baker and I had discovered a few secondary sources to get me started on my research.

The sources I found were informative and introduced me to the idea of the Pack Horse Library scrapbooks. I had briefly read about the scrapbooks in Donald C. Boyd’s article “The Book Women of Kentucky: The WPA Pack Horse Library Project, 1936-1943” and in Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer’s article “Reaching Out to the Mountains: The Pack Horse Library of Eastern Kentucky.” However, it was Jason Vance’s article “Librarians as Authors, Editors, and Self-Publishers: The Information Culture of the Kentucky Pack Horse Library Scrapbooks (1936-1943)” that inspired my decision to research the scrapbooks in more depth.

When I hit another wall in finding scholarly primary sources, I took a detour and went on the Pack Horse Library Wikipedia page to look at the sources used there. I found a lot of newspapers articles from the Great Depression Era that mentioned the Pack Horse Library Project. Some explained what the project was, but others seemed to expect the reader to be familiar with it already. Some of the newspapers did not write full articles but did have advertisements for the Parent Teacher Alliance’s meetings to discuss the Pack Horse Library or to request reading material donations. However, I could not find any newspaper that mentioned the use or circulation of scrapbooks, which I believed would be useful to explore the reception the Pack Horse Librarians received from the public.

I wanted to find images or scans of the surviving Pack Horse Library scrapbooks to use as primary sources, but they all seemed to be behind pay walls, and I had missed the opportunity to request funding for the project. Dr. Alisha R. Knight aided me in this by finding and recommending the University of Kentucky Libraries website, where there is a visual module on the WPA Pack Horse Librarians. This database had a collection of photographs documenting the Pack Horse Librarians work.

Still hoping to find images of the scrapbook pages, I continued both scholarly and informal types of research. On a Google Scholar search, I found a PDF of the 2023 winter issue of The Aquila Digital Community Fonds and Feathers which had a spotlight piece, “The WPA Pack Horse Library Project: A Pioneering Library Service” by Grace Neeley. Looking at Neeley’s references, I saw that her primary source was the Kentucky State Digital Archives website under “Packhorse Librarian Album, 1936-1939.” Here I found high-quality, detailed images of the front and back cover of one of the scrapbooks, plus three of the introduction pages. I had not thought to search the term “album” instead of “scrapbook,” but after trying it in a few different searches I was not able to find more images of the scrapbook pages. In the end, I did not gather all the resources I would have liked to consider in order to answer my research question. However, I found enough to come to some conclusions about what the Pack Horse Library Project’s scrapbooks have to say about the print culture of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression Era.

Findings

Over the course of my research, I made a number of fascinating findings. First, I found out what the Pack Horse Library Project was and why it was created. Then, I discovered the obstacles the librarians faced and what they accomplished. Next, I located information on what kinds of values the people who lived in the mountains of eastern Kentucky had, and how they affected the print culture at the time. Finally, I found out how scrapbooks were used by the librarians with assistance from local residents to gather reading materials and prolong shelf life. All these findings helped develop my answer to my research question, “How do the scrapbooks made by the pack horse librarians display the print culture of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression Era?”

The first finding was what the Pack Horse Library Project was and why it was created. In the 1930’s, as part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to help recover the American economy from the aftereffects Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration (WPA) funded employment on public projects (Schmitzer, iv). Before the first Pack Horse Library Project, 67% of the state population (Scrapbook intro) and 63 counties were without library services (Rhodenbaugh). According to the 1930 Kentucky Census data, the illiteracy in the southeastern counties ranged from 19 – 31% (Boyd, 112). The first page of the Pack Horse Librarian Album introduction says, “The first Packhorse Library was inaugurated in Leslie County in 1934.” When I first started researching, I falsely assumed cars were not yet invented and that bookmobiles would not have been an option. I discovered my error when reading Jeanne Cannella Schmitzer’s article “The Pack Horse Library Project of Eastern Kentucky: 1936-1943” which says, “Bookmobile service reached many schools and communities accessible by road, but could not reach more inaccessible areas and did not serve individual homes” (Schmitzer, 52). This means that the Pack Horse Librarians were only on horses because the remote areas they served were unreachable because of road access or condition. My most heartwarming findings are the stories of how the Pack Horse Librarians improved people’s everyday lives. The librarians would read to people who could not read themselves due to a lack of education or poor physical health. Children would get excited about the arrival of “Book Woman” (Rhodenbaugh). These are just some examples of how impactful The Pack Horse Library Project was; it started as a library extension service made to create jobs and increase literacy rates in eastern Kentucky, but I believe it became a source of hope during hard times.

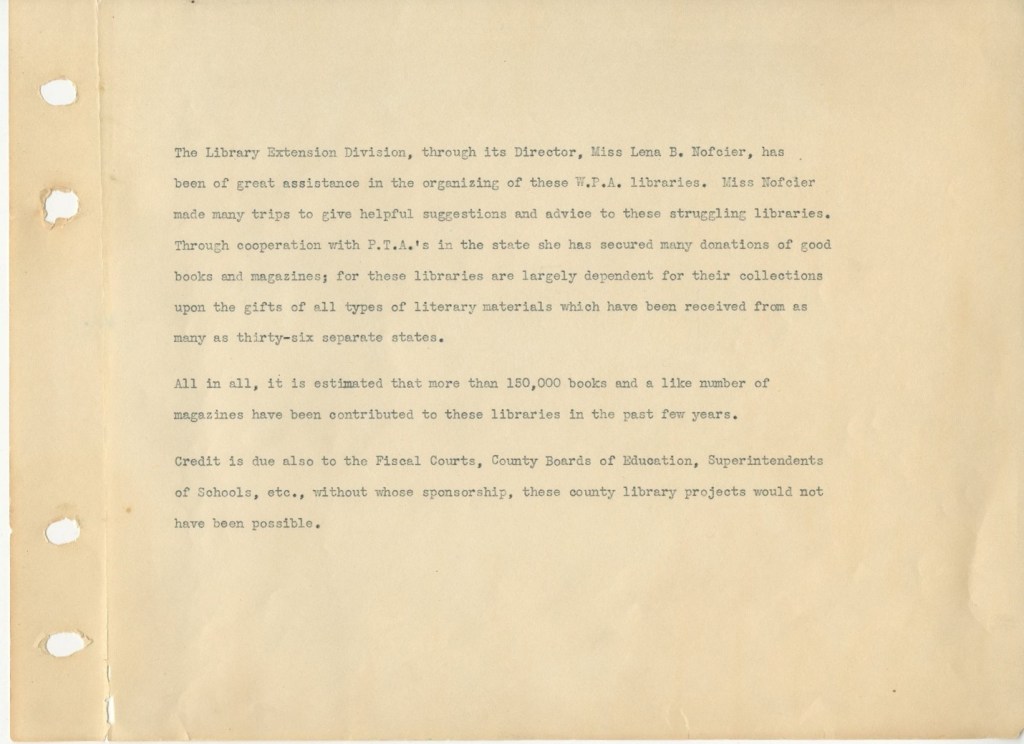

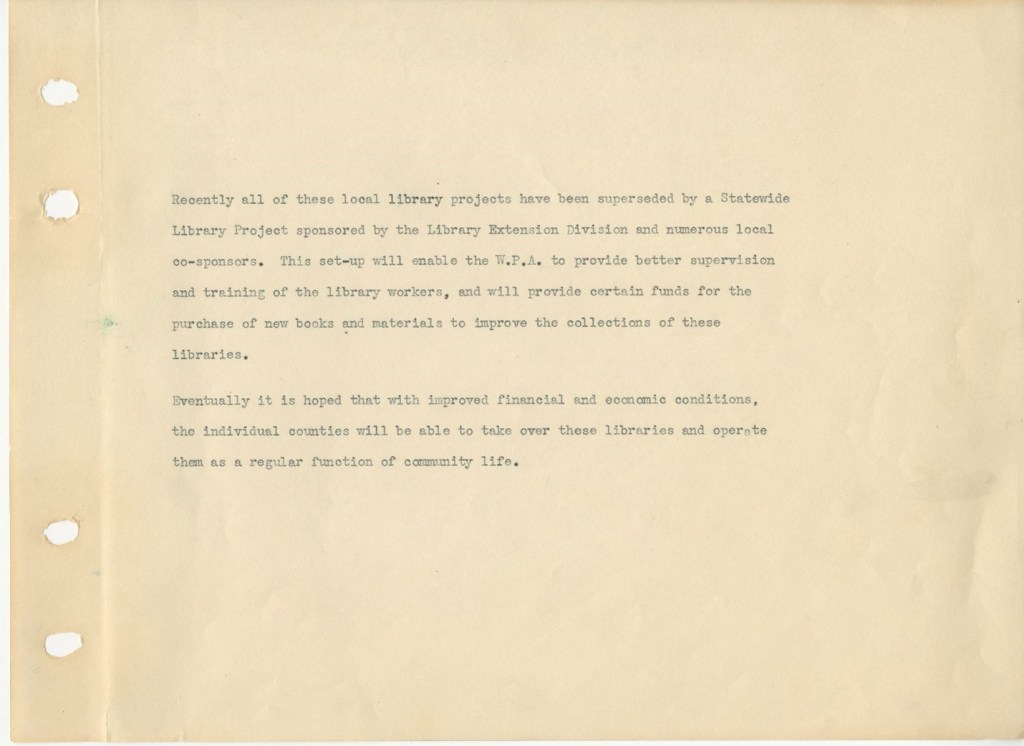

The second finding was the obstacles and accomplishments of the Pack Horse Librarians. One of the big obstacles the Pack Horse Libraries faced was funding. The WPA paid the wages of the librarians: “Each library paid five to seven workers twenty-eight dollars per month,” (Schmitzer, 16). However, there were many expenses that the WPA did not cover. According to Boyd, “Carriers were also required to supply their own horse or mule and to pay for food and boarding of their animals,” (Boyd, 120). Also, the WPA did not cover the cost of reading materials, but according to the Packhorse Librarian Album, Second Page of Introduction, not dated, donations overcame this obstacle. Rhodenbaugh adds to the conversation by mentioning the buildings used as library centers in her newspaper article.

It is possibly true that no other W.P.A. project has been so completely dependent upon the co-operation of the public in establishing itself. For Kentucky Pack Horse Library draws on the Government only for carriers—it does not buy books or rent library buildings. Clubs and other local organizations have supplied centers for the libraries. Books and magazines have come bundles from half the State in the Union (Rhodenbaugh).

It is amazing how the Pack Horse Libraries were able to overcome the obstacles of funding and have such an impact in their community. Another issue the Pack Horse Librarians faced was the initial lack of trust with the people they were trying to serve. It took time and understanding to build trust with the local community so they would accept the reading materials.

The third finding was the kinds of values the people who lived in the mountains of eastern Kentucky had and how they affected print culture at the time. Due to the isolation of the people living in the eastern Kentucky mountains, they were distrustful of the rest of the world. Boyd claims that

Violence as the result of xenophobia, distrust of government as a result of the Civil War, and more recent hostility toward communists and capitalists fueled an evenhandedness with respect to their antipathies, which ‘they have applied to all strangers without regard to race, religion, or nationality’ (Boyd, 113).

Some residents that would refuse the librarians’ reading materials because of their mistrust of government interference. Luckily, WPA policies only employed local people to be Pack Horse Librarians, so the librarians were familiar to the residents. Because most of them were women, they were nonthreatening (Boyd, 120). The residents were also concerned that the reading materials would go against their way of life because “Living a self-sufficient, subsistence lifestyle they had developed deeply set value systems, beliefs, and outlooks through generations” (Schmitzer, 27). To encourage reading, Lena B. Nofcier, the Director of The Library Extension Division, “stressed a selection process that censored out any materials that might offend the mountain sentiments and destroy trust in the service” (Schmitzer, 27), (Packhorse Librarian Album, Second Page of Introduction, not dated). This process heavily affected the print culture of eastern Kentucky because Nofcier requested certain things not be sent while encouraging other types of reading to be donated. According to Edward A. Chapman, who wrote, “WPA and Rural Libraries” in the 1938 October edition of the Bulletin of the American Library Association, novels and fiction were not popular as they were once thought to be sinful. Nevertheless, the residents of eastern Kentucky enjoyed reading stories from “their section of the country” or set in “the cowboy west.” Religious reading materials were in high demand, as were magazines and nonfiction texts that held practical information (Chapman, 708). However, with a limited supply and constant circulation, reading materials wore out quickly. To solve this problem and prolong the circulation life of reading materials, the Pack Horse Librarians started “publishing” scrapbooks.

The fourth finding was how the Pack Horse Librarians used scrapbooks with assistance from local residents to gather and prolong the life of reading materials. In his article “Librarians as Authors, Editors, and Self-Publishers: The Information Culture of the Kentucky Pack Horse Library Scrapbooks (1936-1943),” Jason Vance shows how the Pack Horse Librarians went beyond their traditional role of distributing information until they were in near complete control of the communication circuit in their area. The librarians took books and magazines that were falling into disrepair and cut out parts of the pages to be pasted into scrapbooks. “As part of their work, the librarians would create original scrapbooks for their collections using fragments of discarded books, magazines, reader-contributed stories and drawings, and other printed ephemera” (Vance, 289). This prolonged the circulation of the reading materials without the cost of rebinding or buying new materials. Librarians would make new scrapbooks upon topic request. Vance distinguishes scrapbooks authored by the librarians and those edited by the librarians.

Some of the scrapbooks illustrate how the Pack Horse librarians worked as authors to cobble together hand-crafted works by rupturing and remixing bits and pieces from donated and discarded books, newspaper clippings, and other printed ephemera to create new narratives and texts. Other scrapbooks demonstrate how the librarians functioned more like editors by collecting original recipes, quilt patterns, and stories from their readers, and compiling this contributed content into new collections for distribution along their routes (Vance, 191).

Something I find interesting is that the residents started sharing the information they had to be added to the scrapbooks. On the Kentucky State Digital Archives website, there are photos of the front and back covers and three introduction pages of an undated scrapbook, “Packhorse Librarian Album, 1936-1939.” The front cover is titled “WPA Libraries.” The letters appear to have been cut from leather and attached to the cover with nails, though no materials are listed. The book seems to have been bound in wood with more leather straps and nails near the spine to act as hinges. The inside of the front cover has “Lena B. Nofcier” in the center in faint writing. The first introduction page also has the same name in three different locations, once at the bottom of the page, twice upside down at the top of the page, once on the left and again on the right. These signatures make me speculate that this specific scrapbook was made by or more likely the property of Lena B. Nofcier. Sadly, not many of these scrapbooks survive; while they were valuable to specific people during this era, they were scrapbooks made to collect book and magazine clippings, and were not considered valuable enough to preserve after the Pack Horse Library ended with the WPA. However, I agree with Vance calling these scrapbooks, “‘a material manifestation of memory’ that documented the time, place, and culture of the area in which they were made” (Vance, 291).

To answer my research question, the Pack Horse Library scrapbooks display the print culture of eastern Kentucky during the Great Depression Era by being collections of printed materials that were too valuable to discard. These scrapbooks are material objects that show what information was available and valued by the people living in eastern Kentucky. If the written material was not in line with the values of the residents it would not have passed Nofciers’ selection process. In addition to Nofciers’ selection process the materials added to the scrapbooks would not only have to be available but also thought to have been of value to the community for the Pack Horse Librarians to add into scrapbooks.

Conclusion

The Pack Horse Library Project is definitely an under-researched print culture subject that has so much to offer. The creativity, resourcefulness, and sustainability of the Pack Horse Library Project and librarians can easily be applied to libraries in the 21st century. My project is lacking the sources I wanted, which could have made it a great addition to limited scholarly research on the Pack Horse Library’s effect on print culture in eastern Kentucky after the Great Depression.

In conducting this research project, I learned a great deal about what daily life was like for the Pack Horse Librarians and the residents of eastern Kentucky in the late 1930’s to early 1940’s. I identified a lot of the different terms used to identify the Pack Horse Library Project and related content. I found information on the sad disconnect between archives and ephemera, which says a lot about what the people in charge think is important. From the thousands of Pack Horse Library scrapbooks that were made, so few are left today due to their treatment as ephemera; nobody added them to archives for preservation. I also learned about the reading preferences of the people from eastern Kentucky during the time of the Pack Horse Library Project; I understand why the practical and informative reading material was so popular, but I would like to find more about why fiction was unpopular and considered sinful because it was only vaguely mentioned. Another discovery was the more administrative side of the Pack Horse Library Project: how they received books and how their work week was structured. I learned the most about the scrapbooks made by the Pack Horse Librarians.

Something that I did not locate information on was why books about western cowboys were so popular among the residents of eastern Kentucky. I wanted to know what specific book titles were popular, but that eluded my research as well. I could not find the names of any of the librarians either, which seems strange as they should be on public record because they were paid by the federal government through WPA. I could not find very accurate data on literacy rates during the time of the Pack Horse Librarians, because many of the people reached by the Pack Horse Librarians were apparently not reached by the United States census data and did not go to school. I would like to know more about how well the residents of eastern Kentucky could read.

As previously stated, the Pack Horse Library Project is an under researched print culture subject. I found that many of my sources cited one another, making it clear to me that there are plenty of opportunities for further research on the topic. The first topic that I would suggest for further research is Lena B. Nofcier’s life and work with the project. Because her name was written multiple times on the scrapbook I examined and her name was mentioned in other sources, I can tell that she played a large role. The second topic I would suggest for further research is Mrs. Elenor Roosevelt’s interest in and influence over the Pack Horse Library Project. I found information and a photo that suggests she had interacted with the program and that is why one of the scrapbooks was donated to the Roosevelt Library in New York (Boyd, 118-119) (Vance, 291). The third topic I would suggest for further research is other states inspired by Kentucky that started their own Pack Horse Library Projects. This could lead to huge comparisons. What did they do similarly? What did they do differently? Which states tried it? Are there still geographically or socially isolated areas in America or other countries that could benefit from a Pack Horse Library service? The fourth topic I would suggest for further research is how censorship laws would have affected the Pack Horse Librarians scrapbooks. Did they have to or choose to use citations? Did the librarians write their names in the scrapbooks they helped create or give credit to the residents that provided resources to be added? So many areas are available for additional research to better understand the accomplishments of the Pack Horse Librarians and everything it inspired.

Works Cited

Boyd, Donald C. “The Book Women of Kentucky: The WPA Pack Horse Library Project, 1936-1943.” Libraries & the Cultural Record, vol. 42, no. 2, 2007, pp. 111–28. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/25549400. Accessed 11 Oct. 2023.

Chapman, Edward A. “WPA and Rural Libraries.” Bulletin of the American Library Association, vol. 32, no. 10, (1 Oct.) 1938, pp. 703-709. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/25689501. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Front Cover – outside, not dated. 1936 – 1938. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_757e19b9-0ea8-436f-bad8-0d1495f8690d/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Front Cover – inside, not dated. 1936 – 1938. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_757e19b9-0ea8-436f-bad8-0d1495f8690d/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_1a1fd44f-4699-486f-ba6b-f869ab4e0c79/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Second Page of Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_2232c71f-6e87-46a2-97e9-823493a7de2d//. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Third Page of Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_bbf068a0-b97c-4efb-a8dd-889f3f366d9a/. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

Neeley, Grace. “The WPA Pack Horse Library Project: A Pioneering Library Service.” Fonds and Feathers, Winter 2023, Issue 2, 7-9. https://aquila.usm.edu/fondsandfeathers/2. The Aquila Digital Community. Watson, Emily; and Sims, Andy D., The University of Southern Mississippi Libraries. 6 Dec. 2023. 118 College Dr. 5053, Hattiesburg, MS 39406. Accessed 11 Dec. 2023.

Rhodenbaugh, Beth. “Book Women Started in Kentucky.” The Courier-Journal [Louisville, KY],11 Dec. 1938, p. 78. Newspapers.com, http://www.newspapers.com/article/the-courier-journal/13494378/. Accessed 20 Nov. 2023.

Schmitzer, Jeanne Cannella, “The Pack Horse Library Project of Eastern Kentucky: 1936-1943. ” Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1998. trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2236. Accessed 11 Oct. 2023.

Vance, Jason. “Librarians as Authors, Editors, and Self-Publishers: The Information Culture of the Kentucky Pack Horse Library Scrapbooks (1936-1943).” Library and Information History, vol. 28, no. 4, 2012, pp. 289-308.

Appendix

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Front Cover – outside, not dated. 1936 – 1938. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_757e19b9-0ea8-436f-bad8-0d1495f8690d/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Front Cover – inside, not dated. 1936 – 1938. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_757e19b9-0ea8-436f-bad8-0d1495f8690d/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_1a1fd44f-4699-486f-ba6b-f869ab4e0c79/. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Second Page of Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_2232c71f-6e87-46a2-97e9-823493a7de2d//. 11 Dec. 2023.

Kentucky, State Librarian and United States, Work Projects Administration. Packhorse Librarian Album, Third Page of Introduction, not dated. Kentucky State Digital Archives. M0047-A2009-016-RG1670S. Packhorse Librarian Album – images. Kentucky State Digital Archives, Kentucky Department of Libraries and Archives, 300 Coffee Tree Road, Frankfort, KY, 40601. kdla.access.preservica.com/uncategorized/IO_bbf068a0-b97c-4efb-a8dd-889f3f366d9a/. 11 Dec. 2023.