By Sophia Lennox ’24

Majors: History and Art & Art History; Minors: Gender Studies and Museum, Field, & Community Education

Contributor Biography: Sophia Lennox is a senior majoring in History and Art History, and minoring in Gender Studies and Museum, Community, Field education from West Windsor, New Jersey. She enjoys exploring human connection, historical context, and personal influence in different forms of art.

Brief Description: This paper explores a painting by groundbreaking feminist artist Sylvia Sleigh before she began to explore her craft as a nude portrait artist. It looks at the influence of Sleigh’s personal life, the beginnings of her feminist involvement, and the concepts of autonomy, sexualization, color, and representations of bodies in art.

The following was written for Art & Art History 110: Intro to History of Western Art

Before she became a pillar of the 1970’s feminist art movement in the United States, Sylvia Sleigh was a seamstress who maintained a deep love of painting and art on the side. In her youth, Sleigh was passionate about art; she experimented with different mediums and attended the Brighton School of Art, although she gave up on pursuing it professionally when she started her handmade clothing store in the 1930s.[1] She then met her first husband, Michael Greenwood, and at first, his involvement in the art world as an artist, art history lecturer, and friend of many contemporary artists inspired her to reinvolve herself in painting. After they got married in 1941, she began to paint landscapes, still lifes, and, most importantly, portraits. There is not yet an official catalog of all of Sleigh’s paintings, but from what is currently viewable in museum collections and on her website, there are significantly fewer paintings of Greenwood than any of her other models and subjects. Perhaps there are fewer due to scheduling constraints, her relationship with Greenwood, or the natural development of her craft, but whatever the reason, Sleigh produced very few paintings of him during their marriage.[2] An important one of these paintings is one she painted in 1950 of him in her home in Pett, aptly titled, Michael Greenwood at Pett Rectory (Figure 1).

In Michael Greenwood at Pett Rectory, Sleigh evokes the tradition of Odalisque paintings. As a university educated artist, Sleigh would have been familiar with Ingres’ Grande Odalisque and other paintings like it. She later recalled how frustrated she was with her school only allowing female nude models and not nude male models, feeling as though it was limiting and unequal.[3] In the painting,Greenwood is reclining on a couch or lounge chair that is draped in an ornate and brightly colored granny square crochet blanket. Instead of having a random patterned textile as her background, Sleigh uses a highly recognizable item that evokes a comfortable and homely feeling. Greenwood casually drapes his arm over the armrest of the couch and rests his other hand on his knee, which is bent as he curls his legs up beside him. Instead of feeling seductive like a traditional odalisque, it feels more like he is relaxed and unconcerned. Despite the similarities, there are a number of differences from traditional odalisque paintings that turn Sleigh’s work from emulation into commentary. The most obvious difference is that Greenwood is fully clothed. Although not all of the figures in traditional odalisques paintings are fully nude, if they are wearing clothing, it is usually very little, deliberately placed, or designed to emphasize erotic areas of their body. His pose and posture do not align with what a viewer would expect to see from someone smartly dressed in a color coordinated outfit. If he was visiting a friend, he would likely have his legs right in front of him, maybe one leg crossed over the other. Here, he does not seem like he is in the middle of a catching-up conversation, but in a familiar environment. However, even though he seems relaxed and comfortable, his clothing is still very put together; he is wearing his shoes on the couch, his tie is still tied and tucked into his shirt, and his sweater vest is tucked into his pants. When people come home from a long day at work, they often take off or loosen the more constraining aspects of their outfit, but here, Sleigh made the deliberate choice to make Greenwood almost as dressed as he could be, like he could get up and begin one of his lectures.

Greenwood and Sleigh lived in separate areas of the country for much of their marriage, with Sleigh living in Pett, East Sussex, and Greenwood living in London. While in Pett, Sleigh lived at the Rectory Lodge, which is where she depicts Greenwood in this painting. It can be assumed that the couch Greenwood lounges on is in Sleigh’s living room. Since they lived in different places, Greenwood would have visited this home and his wife instead of experiencing it every day. He is familiar with the home as it is his wife’s living space, but it is not his living space, which puts him in a strange gray area between visitor and regular. By depicting Greenwood wearing his shoes, Sleigh might be showing that Greenwood never fully puts his guard down while in her space, almost like he is feigning comfort and closeness with her. However, instead of representing Greenwood’s hesitation, Sleigh could also be projecting the barrier she felt between her and her husband. By the time Sleigh painted this piece in 1950, she had already met and developed a relationship with her soon-to-be second husband, Lawrence Alloway. Sleigh and Alloway met three years into Sleigh’s marriage in 1944 and developed a close friendship. They eventually married in 1954, the same year Sleigh and Greenwood divorced, which implies that they had some sort of relationship while Sleigh was still married to her first husband.[4] According to the Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo museum in Spain, Greenwood and Sleigh had a complicated relationship. Even though it was Greenwood’s artistic involvement that influenced Sleigh to return to painting, his criticism and “undermining of her confidence as a painter” led to their eventual divorce and her taking another break from creating art.[5] Greenwood’s characterization as someone who made Sleigh feel inadequate in her painting changes how he is perceived in the work. Instead of silent and meditative, his expression could be read as contemplative and critical, perhaps even domineering as he watches Sleigh paint him and judges.

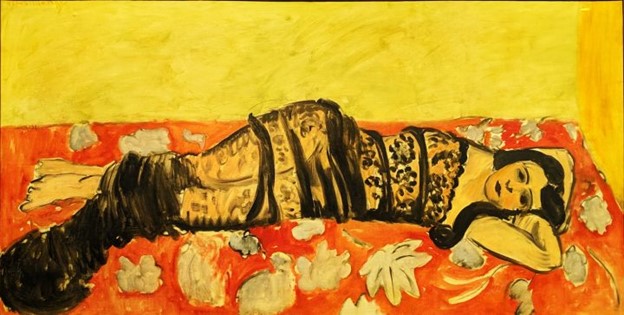

Another painter who worked a few decades before Sleigh, Henri Mattise, experimented with different patterns and textures of textiles in his odalisque paintings. In Mattise’s 1917 painting, The Black Shaw (Figure Two), he depicts a woman called “Laurette or Lorette” wearing a sheer, black, lace dress and lying on top of an orange and gray floral textile. Her black hair, eyes, and dress are in stark contrast to the bright yellow and orange behind her. Matisse outlines her legs and body with thick black lines, and the orange in her chest and thighs separates her body from her more yellow shoulders and arms. Laurette/Lorette stares at the viewer, but she does not have the same expression as Greenwood; her face is blank, almost gloomy and emotionless. Unlike the subjects in Matisse’s work, including Laurette/Lorette, Sleigh’s depiction does not treat Greenwood as a sexual object. Right above Laurette/Lorette’s ankles, Matisse painted the bottom of her dress in very thick, overlapping, tight lines that bind and constrict her movement. The rest of the dress is not painted like that, aside from some darker lines at her hips, furthering the idea that the dress is binding areas of movement but still allowing the audience to see her body through the sheer gaps. Laurette/Lorette’s arms are contorted and tucked behind her head, again seemingly very constricted and putting her in a vulnerable position.[6] In Sleigh’s painting, Greenwood still has his sense of autonomy and individuality. When reflecting on her work later in her life she said, “I liked to portray both man and woman as intelligent and thoughtful people with dignity and humanism that emphasizes love and joy.”[7] Despite Greenwood and Sleigh’s complicated relationship, she still gives him respect and dignity as she would any subject of her work.

After moving to the United States in 1960 with her second husband, Alloway, Sleigh began to create the paintings she would eventually be known for, her portraits of reclining nude men. Michael Greenwood is an early marker of her artistic development, as his posing, facial expressions, and elements in the background are all precursors of where she eventually took her painting. In Michael Greenwood at Pett Rectory, Sleigh balances her relationship with the subject and creates a work that can be understood differently with or without her personal context. In her composition, she includes texture without overwhelming the eye by filling the space to the right of the couch with a patterned glass that mirrors the pattern created by the granny square blanket. As she did with this painting, she continued to subvert viewers’ expectations of traditional art historical tropes and the understanding of the male body in art.

[1] Sylvia Sleigh, ’Sylvia Sleigh Papers’, Collection. Online Archive of California, The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, California. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qc049h/

[2] Estate of Sylvia S. Alloway, “Sylvia, Sleigh, Still Life, Drawings, Women, History”, Accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.sylviasleigh.com/sylviasleigh/Sylvia.html

[3] “Sylvia Sleigh”, Artist Biographies, Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo Museum, accessed December 10, 2023. https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/cultura/caac/descargas/bio_sleigh13B.pdf

[4] Sleigh, ’Sylvia Sleigh Papers’, The Getty Research Institute.

[5] “Sylvia Sleigh”, Artist Biographies.

[6] Lorissa Rinehart, “The Undiscussed Sexual Exploitation Buried in Matisse’s Odalisque Paintings”, HYPERALLERGIC, March 12th, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/489124/matisse-odalisque-norton-simon-museum/

[7] Andrew Hottle, “Biography, Sylvia Sleigh”, Accola Griefen Fine Art, 2017. http://accolagriefen.com/artists/sylvia-sleigh-

Bibliography

Centro Andaluz de Arte Contemporaneo Museum. “Sylvia Sleigh”, Artist Biographies, accessed

December 10, 2023.

Estate of Sylvia S. Alloway, “Sylvia, Sleigh, Still Life, Drawings, Women, History”, Accessed

December 10, 2023. https://www.sylviasleigh.com/sylviasleigh/Sylvia.html

Hottle, Andrew. “Biography, Sylvia Sleigh”, Accola Griefen Fine Art, 2017.

http://accolagriefen.com/artists/sylvia-sleigh-

Rinehart, Lorissa. “The Undiscussed Sexual Exploitation Buried in Matisse’s Odalisque

Paintings”, HYPERALLERGIC, March 12th, 2019. https://hyperallergic.com/489124/matisse-odalisque-norton-simon-museum/

Sleigh, Sylvia. ’Sylvia Sleigh Papers’, Collection. Online Archive of California, The Getty

Research Institute, Los Angeles, California. https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8qc049h/