By Liam Charlotte Siobhan Luckey ’27

Major: History; Minors: English and Theater

Contributor Biography: Siobhan is a history major, prospective English minor, and prospective theatre minor with a deep interest in the value and queerness of many forms of media, particularly teen dramas.

Brief Description: The teen drama as a genre is often looked down upon for its camp sensibilities and the young, female demographics it finds its primary audience. Riverdale is in a unique place within the genre, embodying it more fully than any other show and more ridiculed than any other show. Why it receives this ridicule is a matter of heteronormativity and the deeply queer origins of the language of the teen drama. Riverdale embodies camp, particularly, for the queerness I focus on here, in its portrayals of gender. The men are masculine to a drag-like extreme that challenges the very things it embodies. Riverdale takes its main character, Archie Andrews, derived from the middle-of-the-road, all-American persona of the Archie Comics, and uses him to queer the image of the all-American man and what the American man has looked like over the decades.

The following was written for FYS 101-39: Queer Pop Culture

As a television genre, the teen drama has consistently been overlooked by all types of viewers. To the intellectual and high-brow, the teen drama is meaningless trash TV, its artistic merit and often interesting themes overlooked; to the broad queer audience, the teen drama is heterosexual–focused, and the very often queer creators and the subtexts their queer identities lead to are overlooked by all but a small group of queer viewers. For many shows with little queer presence on prominent online forums such as Tumblr—the heavily subtextually and textually queer Dawson’s Creek by gay Scream writer, Kevin Williamson, for instance—there can be a sense for the queer fan and intellectual such as myself that a further study is necessary in these areas where the queer undertones are obvious to some but completely ignored or never considered by most. The CW’s Riverdale, created by Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa, a gay man, does have a large queer fanbase on Tumblr, but its reception outside of that is so wholly opposite and hateful compared to the fan conception of it that this divide, this need for a new consideration of a text that feels in a way “forgotten”—though it just aired its last episode this past August—is still very much applicable.

As most who listen to what popular culture says will tell you, Riverdale started out good but quickly went downhill. To queer fans, however, the first two seasons are the least interesting, with only one token gay character; they are certainly not as campy or queer as later seasons would become. Here, I will argue firstly for the queer joy and artistic merit of Riverdale, but secondly that hatred for the show may stem subconsciously from heteronormative culture, which associates some of Riverdale’s tone and visual language—rightly—with queerness. The main decision maker on a show being gay is no unimportant factor, and I will be arguing, in hermeneutic fashion, that both the author’s—here, the showrunner’s—intention, or perceived intention, and the viewer’s construction of a personal reading of a text are equally important factors in creating the meaning of a text. Riverdale’s queerness can be explored through its treatment of Archie; Archie’s best friend, Jughead, who serves as the show’s narrator or “author;” their relationship; how their depictions interact with the genre of teen drama; other cultural products Riverdale draws from; and how they compare to the show’s original token gay character, Kevin Keller. By examining the use of subtextual queerness of the characters Jughead and Archie, and textual queerness of the characters Archie and Kevin, it becomes clear how the show uses the cultural products it draws from—namely a few other teen dramas—and its meta-nature to create a singular kind of TV show and a version of the classic teen drama that is by and for queer people. This analysis leads to an understanding of the great artistic value and queer joy of Riverdale, as well as how cultural homophobia and heteronormativity contributed to the intense hatred and ridicule the show’s later seasons receive.

Riverdale is a teen drama television series that ran on the CW Network from 2017–2023 for seven seasons, with episode counts per season usually ranging from 19 to 22 episodes. Riverdale was billed as a gritty take on the classic Archie Comics, which have been running since 1941. The primary concept of Archie Comics is the titular Archie Andrews’s indecision in choosing who he should date: Betty Cooper, the girl–next–door, or rich, bad girl, Veronica Lodge. Rounding out the main cast is Jughead Jones, Archie’s best pal, who is not interested in chasing girls or competing with antagonist character Reggie Mantle, but prefers burgers and slacking off. These four make up the “core four” of Riverdale, a concept that will come up again; it is a character configuration found in many places in media, particularly in teen dramas, and usually consists of two girls and two guys who are variously romantically entangled over the course of the show. As is already obvious, the format is rife with queer possibilities. Riverdale changes these original characterizations significantly; Betty has a dark side and Veronica’s parents are mob bosses, and both girls deal with cruel parents. Veronica’s parents are often out to get Archie and control the town. Betty’s father is a serial killer and groomed her to become one, and her mother reads Betty’s diaries and manipulates Betty and her sister. Archie’s characterization in Riverdale interacts very much with the concept of Archie as “America’s Top Teen–ager” (Pep Comics, 1948) to queer that very idea. Riverdale’s Archie is a victim of abuse and grooming. He’s violent and sensitive. He’s revered by the lens of the narrative, which is Jughead’s lens, as Jughead is framed as the narrator and author of Riverdale, and he is constantly in homoerotic situations. However, Jughead’s TV show characterization is the biggest departure. The CW’s Jughead is intellectual—a writer—but poor and profiled many times in the first season because he comes from the “Southside,” the wrong side of the tracks. His father is the leader of a gang, the Southside Serpents, and Jughead eventually takes up the “Serpent king” mantle when his dad goes to jail. In stark contrast to the Jughead of the comics, who was read by Mark Lipton and many others as a gay character due to his intense hatred of girls, Riverdale’s Jughead kisses girls and dates Betty. Though he is surrounded by queer subtext, it is far less overt than Archie’s. There is a clear reading of Jughead as queer, but one needs to look for it; unlike Archie, he never kisses any boys, nor does he regularly engage in violence with other men, which easily takes on homoerotic and sexual meaning.

The show began its first season as “a moody small-town teen mystery centered on a ‘Who killed Laura Palmer?’–style murder” (Alter), with the core four not the tight group seen in the comics, but split apart. The show quickly became much campier and crazier than that, though, as I will argue, there are hallmarks of the eventual queer madness present in the very first episode. Season two introduces a serial killer, a cult, a gang, Veronica’s mobster father Hiram, the show’s main villain, and the show’s first musical episode. Season three sends Archie to juvie after Hiram frames him and centers around a deadly Dungeons & Dragons-like game and a speakeasy Veronica opens. Season four sees Jughead enrolled at a mysterious private school where everybody is out to get him, with flash–forwards every episode to what is framed for most of the season as the rest of the core four murdering him. Archie opens a community center, becomes a vigilante for the second time, and contends with his father’s death, joining the army at the end of high school[1]. Season five begins with a seven–year time jump to the gang’s lives way past college when they return to Riverdale to clean up the town that Hiram ruined while they were gone. Season six introduces more blatant supernatural horror elements that, this time, really are supernatural: a villain who might be the devil, time travelers, and super powers. Season seven is set in the Archie Comics’ 1950s and puts the gang back in high school, ultimately ending with all of the core four but Jughead having had queer experiences or awakenings. This goes far over the top for a typical teen drama, but it is all greatly informed by the genre.

The teen drama is overlooked and misunderstood as a genre. Due to a lack of academic work on the subject, I will use Corine Elizabeth Mathis’s dissertation, “From Liars to Slayers: Seeking a Better Understanding of the Teen Drama,” as a definitive work on the genre, for, as she writes, her paper “[fills] a gap in current television scholarship” (Mathis, IV). The teen drama is popularly understood to have been founded in 1990 by the show Beverly Hills, 90210, which was created by Darren Star, a gay man. As I define it, the teen drama must define itself by the strictures of the television drama and follow a group of teenage friends who sometimes solve mysteries or fight monsters but are always involved in navigating the teenage issues of grades, dating, and sex. These monsters and mysteries will often serve as metaphors for those other, more personal teenage problems. I would also stress that many new streaming shows with significantly fewer episodes per season do follow many of the conventions laid out by their teen drama predecessors. However, they lack the ridiculous, aimless, dramatic scenarios created to fill in the middling episodes of a 22 episode season, and so, for this reason and others like it, they do not fall in with the rest of the teen drama category. Recognizing that they follow the established conventions too well to be left out completely, they must be included in the genre as they do not fit as well in any other, but the focus in studying Riverdale is on the show as the epitome of the 20–some episode network teen drama “while other teen melodramas of its ilk went the way of the six- or 10-installment streaming series: too long to be a movie, too short for their worlds to feel truly lived in” (Stefansky). As journalism covering the end of Riverdale’s run noted, it was the long seasons that allowed it to be what it was, and it was something that “we’ll never…see again”[2] (Stefansky). I would add to my definition that, above any other subsets, the teen drama must be separated into two huge categories: streaming shows and network shows. When I refer to the teen drama, I am referring, as Mathis is, to the network show.

Mathis sorts her examples of the genre into seven categories, with three major subgenres, the “Family Drama,” “Teen Soap,” and “Young Adult Fantasy Drama,” with three other subgenres to which she devotes less focus, “Coming–of–Age Dramas,” “Multigenerational Soaps,” and “Young Adult Fantasy Soap,” as well as the “Progenitors,” pre–Beverly Hills, 90210 shows that roughly resemble teen dramas. These headings are very useful in fleshing out the multifaceted quality of the genre (Mathis). Though most teen dramas tend towards the over–the–top, those that fall under “drama” rather than “soap,” particularly “coming–of–age” and “family,” such as Dawson’s Creek and Glee as “coming–of–age” and Gilmore Girls as “family,” are more grounded and sincere, striving, in many cases, to teach teens real morals or lessons, although Glee, in terms of set televisual language, falls under both the drama and the comedy category. Those listed as soaps, including Riverdale, are just that; the dialogue is campier, the storylines more ridiculous, and—to paint in broad strokes—the characters will often act older, an oft–criticized element of the genre, unfairly so in my opinion, due to the obvious heightened nature of the shows. Of interest, too, is the “multi–generational” category, which denotes significant plot focus on both the teens and their parents or authority figures. Often, this includes the intrigue of previous or blossoming romantic attachments between the teenagers’ parents, lending an incestuous light to the teens’ own relationships, an aspect more clearly present in Riverdale than most.

So where does Riverdale fit? Mathis, writing in 2017, when Riverdale had just aired its first seasons and had hardly yet defined itself, puts the show under “Teen Soaps.” Her choice highlights both the fluid nature of these useful categories in the teen drama genre where, very often, anything can happen, and Riverdale’s status as a celebration of all aspects of the teen drama, a pop culture amalgam. Today, just months after its final episode, Mathis would sort Riverdale as a “Young Adult Fantasy Soap,” but it moves the characters out of their sophomore year of high school and into their mid–twenties; why not Coming–of–Age? Considering the importance of the characters’ parents and their plots, why doesn’t Mathis sort Riverdale as a “Multi–generational Soap” or a “Family Drama”? Contrasting many of the simple “teens soaps,” of which a common criticism is “Where are their parents?!” Riverdale’s older generation are key players, making the show fit right in with Gossip Girl under “multi–generational.”

I ask these questions not to undermine Mathis’s sorting system but to demonstrate Riverdale’s inability to fit into a box, its embodiment of every different hat that a teen drama may wear. When it was written in 2017, nine of the shows Mathis lists were still on the air, and Riverdale’s seven season run had just started. Now, with the domination of streaming, the genre as we know it is—or seems to be—dying out. When Riverdale ended its run this year, it was on the pages of mainstream, respected publications again for the first time in years as they wrote about it as marking “the end of an era” and described Riverdale as “the last of its kind” (Carr, Alter, Stefansky). The people behind Riverdale seemed to recognize its place as the “last of its kind” seasons ago and it went all out, doing and being everything a teen drama could, a celebration of network television.

As we have discussed, next to the viewer’s personal interpretation and construction of a reading, an author, showrunner, or creator’s intentions, perceived or stated, are an equally vital aspect of a text’s meaning and contribute to the personal interpretation. The creator, directors, and writers, and viewer work together; as Lipton writes, “[a] text is…something woven, and readers join authors as the weavers” (167). To understand Riverdale, the pop culture mash–up it is, we must look at its major cultural contributors. Here, for the sake of brevity, the focus will be on teen dramas, but Riverdale’s strength is that it borrowed from so much more than just these. As Rebecca Alter of The Vulture says, “Riverdale took tropes from gothic horror, fantasy, telenovelas, soap operas, comic books, gay art-house films, dark high-school comedies, musicals, and mafia movies and smushed them together into a pop-culture polycule — while the ensemble held it all together, putting it on like some sort of weekly vaudeville act” (Alter).[3] Teen dramas like Dawson’s Creek, Glee, Beverly Hills, 90210, Pretty Little Liars, and Gossip Girl have prominent influence over Riverdale, down to Beverly Hills, 90210’s star, Luke Perry, playing a major part in Riverdale as Archie’s dad, Fred, until to his death in 2019. The casting for the other parents similarly reflects the show’s major influences, with Scream star Skeet Ulrich representing the show’s slasher roots, which are also present in Pretty Little Liars, as Corine Mathis argues, and Mädchen Amick who starred in Twin Peaks representing the show’s most major influence in setting, tone, plot, and themes outside of the teen TV genre. It is important, then, to look at how many of these projects have gay creators: the 1996 movie Scream, written by the openly gay Kevin Williamson, who also created Dawson’s Creek,and every teen drama listed above except for Pretty Little Liars. Beverly Hills, 90210, the very origin of the teen drama, is queer in origin; the creator was gay and based it roughly upon his own youth (Itzkoff), which casts queer light over all the staples Beverly Hills, 90210 created. As Mathis states, “Beverly Hills, 90210…created a distinct place for the genre, establishing conventions and expectations for the audience that still exist today” (8), most importantly “[establishing] the grammar audiences expect to see today” in terms of character (Mathis, 84). The blog riverdaleheritageposting on Tumblr serves as a good source for the volume of people on Tumblr engaging in queer readings of Riverdale. Though it primarily compiles posts that err more on the humorous side, most of the blogs that shown there have made deeper analysis posts. If so many character conventions and interactions within teen dramas are read as queer by groups of queer youths online searching in the perfect place to “[create] a group of friends from fiction” (Lipton, 171), it makes sense that this character “grammar” (Mathis, 84) stems from a show created by a gay man. This suggests a strong argument for the queerness inherent in the subtext of every teen drama following Beverly Hills, 90210’s lead.

Riverdale, while based on the Archie Comics, carries influences from Dawson’s Creek, which centers on a core four and a love triangle that feels lifted directly from Archie Comics (Lloyd). It interacts with its source material in layered ways, creating multiple new characters out of Archie, Jughead, Betty, and Veronica. One version of the 82-year-old characters it interacts with is show creator Roberto Aguirre Sacasa’s own play, a product of his life–long passion for Archie Comics. Sacasa, who is openly gay and became chief creative officer of Archie Comics in 2013, received a cease and desist from Archie Comics in 2003 for a play he was staging in which Archie Andrews came out as gay and moved to New York (Kaplan). In the play, titled Archie’s Weird Fantasy, the town of Riverdale was a representation of the closet, and Archie leaving for New York was vital to his ability to be himself. Written and directed by Sacasa, who would go on to create and hold chief creative control over Riverdale—which, whether you read Archie, Jughead, Veronica, or Betty as queer up until season seven or not is still an undeniably major queer departure from the 1950s wholesome all–American-ness and sentimentality of the Archie Comics—Archie’s Weird Fantasy is the most vital aspect that needs to be taken into account when looking at Riverdale’s representations of the comics’ core four.

The Characters

In order to discuss the characters I chose to focus on—Archie, Jughead, and Kevin—I will focus primarily on the first episode of the series, and the back half of its final season. These seasons endeavor the most to appear similar to typical teen dramas on the surface, with few fantasy elements if any at all, and, in season one, few of the other ridiculous Riverdale hallmarks that made the show so fun and campy. The most focused on interpersonal relationships, seasons one and seven lend themselves the most to a rudimentary queer analysis, although the visual and aesthetic queerness and larger plot influences of the intervening seasons are very much worth exploring in a larger format. Though seasons one and seven appear the most palatable, their queerness is just as blatant, and the meta nature and camp essential to the bulk of Riverdale is certainly present in season one and becomes more and more the very focus as season seven goes on. In terms of season one, I will be focusing on the moments of Riverdale’s pilot episode which I view as first indicators of the queer madness and queer perspective the show would come to exemplify. Season seven, particularly its latter half, pulls out all the queer stops. Many shows that make characters queer at the very last moment are accused of trying to appeal to “the gays” as soon as it won’t hurt their revenue any more, but Riverdale wasn’t making nearly as much by the end of its last season and certainly had no hopes of returning to its season one popularity. The way it went about making the characters queer was clearly not trying to appeal to anyone who hadn’t already been a fan. A look at the entirety of Riverdale’s run will clearly show the viewer that a queer Archie was present in the subtext long before he told Reggie, “you know, there’s an in–between,” and confirmed himself, in some terms, as bisexual in one of the final episodes; later in the episode, he does say “I love you” to Reggie.

“Is Being the Gay Best Friend Still a Thing?” Kevin Keller’s Critique of the Token Gay

Though a huge focus of this paper is on Riverdale as subtextually and aesthetically queer, there is a male main character, Kevin Keller, who is queer from the first season, though several of the male series regulars—Kevin, Fangs, Archie, and arguably Reggie—are eventually queer characters by the end. Kevin is, for seven seasons, not much more than a joke and an archetype. In the first episode, Cheryl Blossom, who would eventually become the show’s lesbian main character, describes Kevin as “the gay best friend”—the full line:

Kevin (to Cheryl): Is cheerleading still a thing?

Cheryl: Is being the gay best friend still a thing?!

—calls the show out for flattening him to his sexuality. Kevin fits the stereotype; a few episodes later, Veronica calls him her “best gay.” He is the gay best friend, a little behind, or just at the end of, his time in 2017, and he satisfies a hunger for representation as much as any of them do, if not less, because he is never given a personality outside of being gay. However, they are not playing this archetype straight. Kevin, in my view, is not supposed to be good representation, but rather to mock the “gay best friend” trope and to emphasize the need for a queer Archie, a queer Veronica, a queer Betty, and a queer Jughead.

I connect Kevin’s depiction in 2017 as a character who is not much more than his sexuality to Kurt’s nuanced portrayal in Glee, which began eight years before Riverdale and involved many of the same people. Both shows had gay people behind the scenes, and Kurt and other Glee characters after him set the precedent that a gay character in a teen show could be much more than a flat stereotype there to make the show look good and gossip with the straight female protagonists. The comparison to Kurt makes it clear that just like the many other ways Riverdale plays with the conventions of the teen drama, Kevin is a deliberate critique of the gay best friend character, which that scene in the first episode clearly argues belongs to a bygone era.

Archie’s All–American

As we have established, Riverdale, like most teen dramas, comes from a gay perspective; the creator, and thus the creation, is gay, along with the motivation, Archie’s Weird Fantasy. The points of reference, inspiration, and homage are queer as well. Knowing this, or even merely sensing it, a queer viewer sees the lightly obscured goal of Riverdale. It takes Archie, an all-American wholesome teen, and makes him the epitome of the American man, in actions if not in personality and mind. This too is a source of queerness in the show–the struggle and opposition within Archie; he is at first a football player, then a vigilante, a wrestler, a mobster, a prisoner, a boxer, a soldier, a miner, a union man, and, at last, a basketball player who goes against his uncle’s enforcing of masculinity to become a beat poet and build the interstate highways. At the same time, Archie is the center of the homoeroticism present in the show. Teen dramas are very heterosexual on the surface, but with the subtext and through their writers’ identities, much covert queerness comes in. Riverdale is a show that brings the subtextual queerness that is not uncommon in teen dramas to the extreme. Archie, thus, is a queering of the “all-American” man he always represented, in some vein, in the comics.

At the same time, Archie has a source of queerness in his internal struggle. Seasons one and seven give us his internal High School Musical conflict. In the first, his struggle is football vs. music. Then, in the seventh season, it comes back much more queer and, suddenly, the question of “basketball vs. poetry” is visually, explicitly meant to imply both “girls vs. boys” and “Reggie vs. Jughead,” when, in a musical number, Archie laments not being able to choose between two things. The song is supposed to be about his choice between Betty and Veronica this question, again, being always at the center of the Archie Comics, but, as he tells Kevin, who is writing this musical about his own friends, this conflict doesn’t really ring true for him; it is not the choice he faces in real life. Similarly, in the imaginary musical sequence, things take a turn and as Archie sings, “how can I choose between two perfect things?” the camera and his eyes stray from him hanging with Betty to Reggie playing basketball, and then from Archie and Veronica in a booth at the diner to Jughead at his typewriter. It is a choice between “basketball” and “poetry,” poetry exemplified as queerly as possible by the Beats here, Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl,” specifically. Archie’s uncle speaks disparagingly of Archie’s poetry in as close to implied gay bashing language as the CW is going. Uncle Frank makes it clear over and over that to him it is “poetry vs. girls.” At the end of the musical episode, Archie defies his uncle’s homophobia, choosing poetry and quitting the basketball team; a few episodes later, Archie and Reggie watch gay porn and have a threesome together.

Though this example of Archie’s queerness is from the final season, it is merely the culmination of six seasons of subtextual queerness and two gay kisses. Betty and Veronica can kiss, and Archie can have something at least gay sex-adjacent in season seven because the framing device for the 50s setting allows them to be characters who are at the same time new and old. They are the ones we have been watching for six seasons, but they are not. Season seven explores its cast as Archie comics characters, as archetypes, as their Riverdale selves, and as the characters from Sacasa’s 2003 play.

“I Would’ve Done Anything to Protect Archie”: Jughead’s Homosexual Obsession and Internal Hatred

Jughead is just about the only one of his friends to come out of Riverdale’s final season seeming completely heterosexual to the heterosexual viewer. Why is this? We also leave Archie with a wife. In my view and the view of many queer fans online, Jughead and Archie’s eternal place standing just a step away from canonical queerness is all part of the larger Riverdale theme of the characters not truly being able to escape the cyclical town and physical location of Riverdale, which, in the 2003 play, represented the closet.

Riverdale makes Jughead the narrator, not a burger-eating dummy, but a self-described “intellectual” and film snob from the wrong side of the tracks who does kiss girls and enjoys it. Perhaps it’s just that for a TV show where consistency mattered, Jughead as an available love interest for one of the girls would serve the show better in keeping both Betty and Veronica in the main circle, but it is a marked deviance from the comics, where Jughead’s defining traits are his laziness, interest in food, and disinterest, even disgust, towards girls, which made him perfect for queer readings, and which makes his Riverdale incarnation’s staunch heterosexuality such an odd deviance. Of course, he still has his “[subtextually implicit] love of Archie” (165), which Lipton describes. As narrator and writer of the story, Jughead centers Archie as the main character. The second sign in that first episode of what I call the eventual queer madness comes near the end. Jughead, until now, has been present in the episode only in the background, for brief shots here and there, in addition to opening the episode in voice over as he types at a laptop. Archie, in one of the last scenes, is shown standing outside the diner; he is looking for Betty because he kissed Veronica and she ran off. “He was looking for the girl next door,” Jughead tells us in voice over, “instead, he found me.” Thus, Jughead enters the story as more than an observer because Archie found him in the diner.

The ensuing scene introduces the falling out that the two start the show having had over the summer, although it will not be explained until the next episode. They are fighting but still talk like two old friends. Archie confides in Jughead his existential worries about the death of their classmate Jason Blossom, the show’s inciting incident, our “Laura Palmer.” Archie’s feelings over the event have appeared complicated all episode, but only here, to Jughead, does he express them. Then, the conversation turns to Betty: “I think I lost my best friend tonight,” Archie says. Jughead gives him a funny look and responds, “‘If you mean Betty…just talk to her, man. That would go a long way’ (then) ‘Would’ve gone a long way with me.’ end scene.”

This scene sets everything up. Jughead is telling Archie’s story, which is why he doesn’t tell us about the falling out until Archie does, he’s obsessed with him—see: in love with him—yet always resentful of him, at first for the cause of the falling out, but, ongoingly, for the same things he’s obsessed with—see: attracted to—about him and that he as narrator forces him into: his all-American masculinity. They’re both mired in homoerotic and homoromantic subtext, but Archie is more free to act on it without retribution because of his masculinity. How can Jughead be jealous of Archie over subtext? That’s just the meta nature of Riverdale—Jughead knows all about the subtext; he’s the author.

While Kevin represents and critiques the flatness of characters designed solely to function as gay representation, Betty, Veronica, Jughead, and Archie fight in the subtext and text against the town of Riverdale and the Author, Jughead, which play the role of Comics Code Authority, MPAA, Hay’s Code, and studio executives, to be real, human, and queer—and they almost make it.

The nature of Riverdale is that it will not let them. The inciting incident, Jason Blossom’s death, sets up the narrative. Resembling Archie, he was a redhead quarterback who tried to escape Riverdale, to get away across the river. He doesn’t make it; the town will not let him. Many times, throughout the seasons, we see barriers and blockades set up at Riverdale’s borders and people murdered near the town sign or in the forests on the outskirts. When a comet is about to hit the town. there is no discussion of the outside world, whether there will be effects on it. Does it really exist at all?

If Riverdale is the metaphorical closet, then the absence of an outside world altogether helps it serve as a good allegory for the shutting out of queer main characters from media, their eternal trapping in the subtext through social and cultural homophobia, Archie’s dad’s apprehension about his music in S1 and his uncle’s poetry-related homophobia in S7, censorship, explored in seasons two through six and explicitly with the town’s administrators issuing a “comics code” in season seven, and through what Lipton calls “Jughead’s tendency toward self-hating homophobia” (166). “We’re not gonna hug in front of the whole town,” he tells Archie in the second episode after they make up, “so why don’t we do that bro thing where we nod like douches and mutually suppress our emotions.” Jughead is more aware of himself; unlike Archie. who acts like he’s discovered something brand new when he’s somewhat confirmed to be bisexual in the last season, Jughead knows that he is “weird, [he is] a weirdo.”

The show’s reception over the years mirrors the distaste for queer media. Its quality past season one has been widely rejected by popular culture; most responses to “what do you think of Riverdale?” are, if people have seen it, then “I stopped watching after season one, or two, or three—it just got too crazy.” There is an intense hatred for the show not proportional at all to the reality of what it is, coming mainly from those who have hardly seen it but maybe have heard headlines about what is going on with it these days. A lot of cultural heteronormativity contributes to this perception and reception. It is first the misunderstanding, failure, or unwillingness to understand that what they’re laughing at is deliberate camp, meant to be laughed with. Due to camp’s close association with queerness, I chalk this up to heteronormativity and subconscious hatred of things associated with queerness. In this vein, the queerer episodes—the musical episodes—get consistently far lower episode by episode ratings (IMDB).

Queer Joy: Archie’s All–American Critique of Masculinity

As I discuss the queer joy of Riverdale, my focus will be, hermeneutically, on what queer viewers get out of the show, referring almost exclusively on Tumblr fandom due to the odd place Riverdale occupies in popular culture. The show is a household name, with its first season garnering a huge viewership. Everybody knows about “I’m weird, I’m a weirdo,” and “the epic highs and lows of high school football,” but the show is still, in a way, obscure. Those who are actually fans of all of the seasons or even the majority of the seasons and are vocal about it on social media; they are either hate–watchers, straight fans invested only in the season one and two ships over plot points, analysis, or even fun, or queer Tumblr fans. Though Riverdale started off with a very heterosexual reputation it has not quite been able to shake, saying you are a Riverdale fan to fellow fans almost implies queerness. I, myself, started watching in the spring of 2022, partly because of intriguing posts I had seen on Tumblr.

For many, including myself and users on Tumblr, the appeal of Riverdale and its queer subtext comes from the following; much of the enjoyment derived from the show comes from its elements of many genres and from getting to see queer characters in those genres. The show puts the queer characters, or heavily, subtextually queer characters, into absurd, dark, and complex situations and stories that exist partly because of their queerness. Cheryl’s parents’ disapproval of her sexuality, for instance, is uniquely compelling compared to the typical story queer viewers may be tired of because it is presented is through the lens of the gothic, which Cheryl typically inhabits. Characters’ subtextual and textual queerness is an important part of the plot, but it is also far from the whole plot. There is a multifaceted nature to the queer representation or interpretation not seen much elsewhere. Very few characters on the show are not mired in queer subtext, because the show has such a sense of coming from a queer perspective and speaking directly to the queer viewer, which increases its appeal. Since everything that happens to Archie is tied to his subtextual queerness, the absurd darkness of his story through the sports, crime, or general Americana genre lens is an exciting queer critique of the all–American man through a queering of every masculine American pop culture staple.[4]

Everybody wants Archie: Jughead, Veronica, Betty, Veronica’s father, the devil, Reggie, Kevin, his music teacher Ms. Grundy, his fellow juvie inmates Monroe and Joaquin, the warden at juvie, and even Cheryl, the show’s lesbian. He is somebody different to everyone, always drawing from Jughead’s vision of him; the imposition of figures on him is part of the undercurrent of an abuse narrative that surrounds him, which starts in the first season with his “affair” with Ms. Grundy when he is sixteen. Betty’s busybody mother forces her out of town when the “affair” is found out, a plotline shown mostly to break Archie’s heart. On the surface, Riverdale’s treatment of the student-teacher relationship resembles many others seen in teen dramas, which them as forbidden, desirable, and certainly not grooming. Pretty Little Liars pairs a female high school student and male teacher. Dawson’s Creek couples teenage Pacey, who suffers from a lack of parental oversight just as Archie does, with the much older Tamara, who is first seen coming into the video store where Pacey works and turns out to be his English teacher some scenes later. Neither of these shows paint the relationships as an older person in power taking advantage of a much younger, underage person. Nevertheless, some of the lines delivered by the groomers do resemble abusive or manipulative language, and neither Pacey’s life in Dawson’s Creek nor all of the happenings in Pretty Little Liars are supposed to be ideal.

Archie also suffers from a lack of parental oversight, but Riverdale presents those aspects of its characters’ stories differently, not saying any of the serious truths too blatantly. However, working under the idea of artistic intentionality—that every element is present for a reason—Archie suffers repeated abuse following Ms. Grundy’s treatment of him and as a result of it; I believe it is a deliberate thread within the show and the most prominent aspect of Archie’s narrative. It is interrelated with his queerness and it is buried, just as his queerness is buried, to maintain the image of the all–American boy, consciously by Archie taking up wrestling and boxing in order to become tougher instead of facing his demons, and more subtly by the author, Jughead, representing heterosexual storytelling and censorship, and the town of Riverdale at large.

Ms. Grundy is presented differently from the groomers of Pretty Little Liars and Dawson’s Creek. Yes, she escapes condemnation partially because Archie is a boy and because it was 2017, but I believe the plotline was always an effort to subvert the trope. She is killed early in season two for being a “sinner” by a serial killer terrorizing the town in order to “cleanse” it. Though most of his murders or attempted murders take Puritan definitions of sin, such as attempting to murder Archie’s dad for “adultery” and two of Archie’s schoolmates for drug use, the method of her murder is different. Instead of shooting her, the killer strangles her with a cello bow gifted to her by Archie. In season six, the show revisited the topic of Ms. Grundy for an episode, showing Archie’s trauma from the situation. Yet Archie’s trauma is already clear, according to queer Tumblr fans’ analysis, through his relationship with Veronica’s father, main Riverdale villain Hiram Lodge. In season two, Archie is involved in mob activity with Hiram, and their relationship carries much of Archie’s homoerotic subtext for the season. The widespread queer fan interpretation of Hiram on Tumblr is another person who groomed and—subtextually sexually—abused Archie, as referenced in Tumblr user ultimatewildcard’s post.)

I bring in Archie’s abuse narrative to show the vulnerability and complexity of Archie’s character that make him so appealing to queer fans and to demonstrate the ways in which meaning and narrative in Riverdale operate on two separate plains: that which is stated repeatedly in the show’s typical over–the–top fashion—the larger plot points and the personal motives and emotions that the characters actually discuss—and that which goes undiscussed but which makes up a huge, repeated current in the show: Archie is manipulated and groomed repeatedly and is a victim of abuse; Veronica is in a “love triangle” between her boyfriend and her father; Betty’s family is a picture of the corruption inherent in the suburban nuclear family, similar to Twin Peaks’ Palmer family without the incestuous rape. The entire show is about TV shows and storytelling; the fact that the characters exist as characters in a story is nearly a real element of the text. Both Archie’s abuse narrative and his queerness operate within the latter, as does Jughead’s homosexual idolization and obsession with Archie through the lens of his narration of the show. Do queer aesthetics and undercurrents make for a show that truly does something for the advancement of queerness? Many teen dramas simply employ queer aesthetics and keep their queerness to the heavily implied; as we’ve discussed, many teen dramas are, in some sense, queer. Recognizing queer subtext can be rewarding, but it can become tiring and frustrating. Representation cannot survive on queer subtext and gay best friends alone—and Riverdale, as I have illustrated, argues this claim. Queer fan frustration is a common occurrence; personal interpretation alone is not enough. Riverdale feels different to many queer fans. Riverdale feels like it is on the queer fan’s side. It comes from a perspective of knowing the frustration of always seeing Kevin’s or Archie–and–Jughead’s or Betty–and–Veronica’s. Riverdale does not frustrate. It winks and nods to the queer viewer with details like Archie’s juvenile detention facility being named after Leopold and Loeb, its camp musical numbers with songs from Rocky Horror, Cabaret, and Anything Goes, and queer filmmaker Greg Araki’s directing of “The Wrestler,” possibly the show’s most homoerotic episode, in which Archie wrestles Hiram and Kevin is on the wrestling team. However, it also makes every one of the main characters queer, with the exception of Jughead and Tabitha, and puts the core four in a polyamorous relationship in the last episode. Most teen dramas employ queer aesthetics, with only some subtext or a gay best friend. Nevertheless, in light of the final season, Riverdale is genuinely arguing for the right of its main characters to be gay, that they should be, but something is holding them back.

[1] Archie’s joining the army is very important to his characterization as a critique of and queering of the “All–American man.” The war he fights in is ambiguous and certainly not period–appropriate for the 2020s, the uniforms and trench warfare resembling the first World War. As Tumblr user beronicalongcon states in a post from August, 2023 discussing a scene that’s been laughed at a lot where Archie dreams of serving in the war and it’s set on a football field in these anachronistic uniforms, “”Haha football war” shut up this is one of the most artistically cohesive and interesting sequences in the entire series. It lays bare the twisted knot of dream logic and aestheticism that governs Riverdale’s universe. “Why do all the visual cues point to Archie fighting in WWI if Riverdale is set in 2021?” Because WWI was the period where America most successfully fetishized the IMAGE and AESTHETIC of young men going to war as a MASCULINE IDEAL. “Why are they fighting on a football field?” Because football is another heavily fetishized mode of expressing American masculinity and violence as heroic. “Why is Jughead there?” Because Archie loves Jughead.”

[2] To demonstrate the volume of this sort of language in journalism covering the show’s ending, here are many examples: The Ringer: “It’s the last of its kind,” The Vulture: “one of the last of its kind: the 22–episodes–a–season teen soap,” AV Club: “The end of Riverdale is the end of an era of television,” “We may never see this kind of zany teen soap ever again,” EW: “The world where a network lets a sexy teen genre drama run off the rails for seven gloriously outlandish seasons no longer exists.”

[3] More useful accounts of Riverdale’s nature: Abby Monteil of Rolling Stone describes it as “eager for reinvention,” “a campy, Frankensteinian mash-up of genres, pop-culture references, and pie-in-the-sky melodrama that’s frankly unlike anything that came before it.”

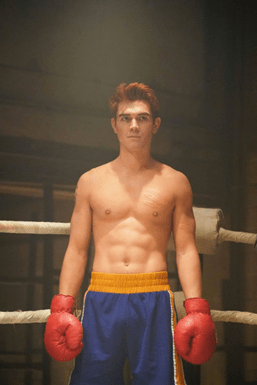

[4] See image for an example of Riverdale’s aesthetic queerness and how Archie is visually represented as the “all–American” man, a hypermasculine, drag–like parody of masculinity. To drive home the parodic nature, the scars on his chest are from literally being attacked by a bear and living.

Works Cited

Aguirre-Sacasa, Roberto, creator. Riverdale. Berlanti Productions, Archie Comics, CBS

Studios, Warner Bros. Television Studios, 2017-2023.

Alter, Rebecca. “They’re Finally Ready to Graduate.” Vulture, New York Magazine, 15 Aug.

2023, www.vulture.com/article/riverdale-cast-exit-interview.html. Accessed 13

Dec. 2023.

Baldwin, Kristen. “Farewell to Riverdale — and the CW as we know it.” Entertainment Weekly,

24 Aug. 2023, ew.com/tv/tv-reviews/riverdale-series-finale-review-goodbye-riverdale.

Accessed 13 Dec. 2023.

Beronicalongcon. “MY TOP 10 RIVERDALE MOMENTS.” Tumblr, 23 Aug. 2023,

www.tumblr.com/beronicalongcon/726486293414117376/my-top-10-riverdale-mo

ments. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023.

Carr, Mary Kate. “The end of Riverdale is the end of an era of television.” AV Club, 21 Aug.

2023,_www.avclub.com/the-end-of-riverdale-is-the-end-of-an-era-of-television-18

50747885. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023.

Driver, Susan Mark Lipton. “Queer Readings of Popular Culture: Searching [to] Out the

Subtext.” Queer Youth Cultures, 2008.

Fagaly, Al. Archie – America’s Top Teen-ager in Pep Comics. No. 67. May 1948.

comicbookplus.com/?dlid=71120. Accessed 15 Dec 2023.

Itzkoff, Dave. “DARREN STAR, creator, ‘Beverly Hills 90210.’” New York Times, 29 Aug.

2008._www.nytimes.com/2008/08/31/arts/television/31star.html?_r=1&scp=10&s

q=Beverly%20Hills,%2090210&st=Search. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Kaplan, Avery. “The Weird History of Roberto Aguirre–Sacasa.” The Beat: The Blog of Comics

Culture, 3 June 2019, https://www.comicsbeat.com/roberto-aguirre-sacasa-weird-history/.

Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Lloyd, Robert. “Without a Paddle.” LA Weekly, 29 Jan. 1998,_www.newspapers.com/article/la-

weekly-dawsons-creek-season-one/72709686/. Accessed 15 Dec. 2023.

Lynch, David and Mark Frost, creators. Twin Peak. Lynch/Frost Productions, Propaganda Films,

Spelling Television, 1990–1991.

Mathis, Corine Elizabeth. “From Liars to Slayers: Seeking a Better Understanding of the Teen

Drama.” MTSU Doctoral Dissertations, 2017.

Monteil, Abby. “‘Riverdale’: 20 Wildest Storylines Ranked, From Superpowers to Cults.”

Rolling Stone, 22 Aug. 2023. https://www.rollingstone.com/tv-movies/tv-movie-lists/

riverdale-20-wildest-storylines-ranked-cw-cole-sprouse-lili-reinhart-1234810121/kevins-t

ickle-videos-1234810120/. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023.

Murphy, Ryan, Brad Falchuk, and Ian Brennan, creators. Glee. Brad Falchuk Teley-Vision, Ryan

Murphy Productions, 20th Century Fox Television, 2009–2015.

Riverdaleheritageposting. Tumblr, www.tumblr.com/riverdaleheritageposting. Accessed June

2023.

Star, Darren, creator. Beverly Hills, 90210. Propaganda Films, Spelling Entertainment/Spelling

Television, 1990–2000.

Stefansky, Emma. “We’ll Never See Anything Like ‘Riverdale’ Again.” The Ringer, 22 Aug.

2023, www.theringer.com/tv/2023/8/22/23841050/riverdale-last-episode-series-fi

nale-season-7-archie-comics. Accessed 13 Dec. 2023.

Ultimatewildcard. Tumblr, 26 Nov. 2022,https://www.tumblr.com/theultimatewildcard/

701966783988498432/i-regret-you-all-the-time. Accessed Dec. 2022.

Williamson, Kevin, creator. Dawson’s Creek. Columbia TriStar Television, Outerbanks

Entertainment, Sony Pictures Television, 1998–2003.